Between 1346 and 1351 the Black Death swept across Europe. First from the east along trade routes to Italy before spreading to northern Europe and Britain.

In all up to 200 million people died, somewhere between one and two thirds of Europe’s population. It was a horrible way to die; victims suffered fevers, bloody coughing, extreme pains and the characteristic ‘buboes’ or swellings full of pus.

For the people of Europe at the time it must have been like the end of the world. When COVID-19 first struck most people, while scared, had at least some rudimentary knowledge of germs and how disease is spread. This was not the case in the 14th century, some 400 years before germ theory would emerge. Doctors might have their own individual theories but couldn’t offer much hope. As a result people turned to the church.

This made sense. The Bible speaks of plague as the work of God and so the Catholic church, the dominant religious power in Europe, was expected to provide answers. As people died priests were to become the key workers of the Black Death, providing what comfort they could and, importantly, performing the Last Rites to ensure passage to Heaven.

Unfortunately, this put the priests at great risk. Without any form of PPE they would often fall victim to the Black Death themselves. It’s estimated that 42-45% of priests died from the Black Death. In 1348 six cardinals would die.

The head of the Catholic church at the time, Pope Clement VI, therefore faced an unprecedented challenge: how best to provide spiritual leadership and ensure salvation for people. Born Pierre Roger in 1291, he had been Pope since 1342. He was the fourth Avignon Pope - a series of seven popes between 1309 to 1376 whose court sat in the French town of Avignon rather than the Vatican. The wine Châteauneuf-du-Pape (the Pope’s new house) dates from this period and is still made in the region today, its name signifying its papal legacy.

In facing the Black Death Clement VI was pragmatic. As grounds for burial began to run out he consecrated the River Rhône in 1349 so that the bodies of plague victims could be disposed of there. He granted the remission of sins of all of those who died from the plague so even if they couldn’t confess their sins and receive the Last Rites their souls would be safe. As fear mongering led to the blame and persecution of Jews he issued two papal bulls in 1348 denouncing anti-Semitism. On 26th September 1348 he issued Quamvis Perfidiam in which he called on Christians to protect Jews:

“certain Christians, seduced by that liar, the Devil, are imputing the pestilence to poisoning by Jews…“since this pestilence is all but universal everywhere, and by a mysterious decree of God has afflicted, and continues to afflict, both Jews and many other nations throughout the diverse regions of the earth to whom a common existence with Jews is unknown (the charge) that the Jews have provided the cause or the occasion for such a crime is without plausibility.”

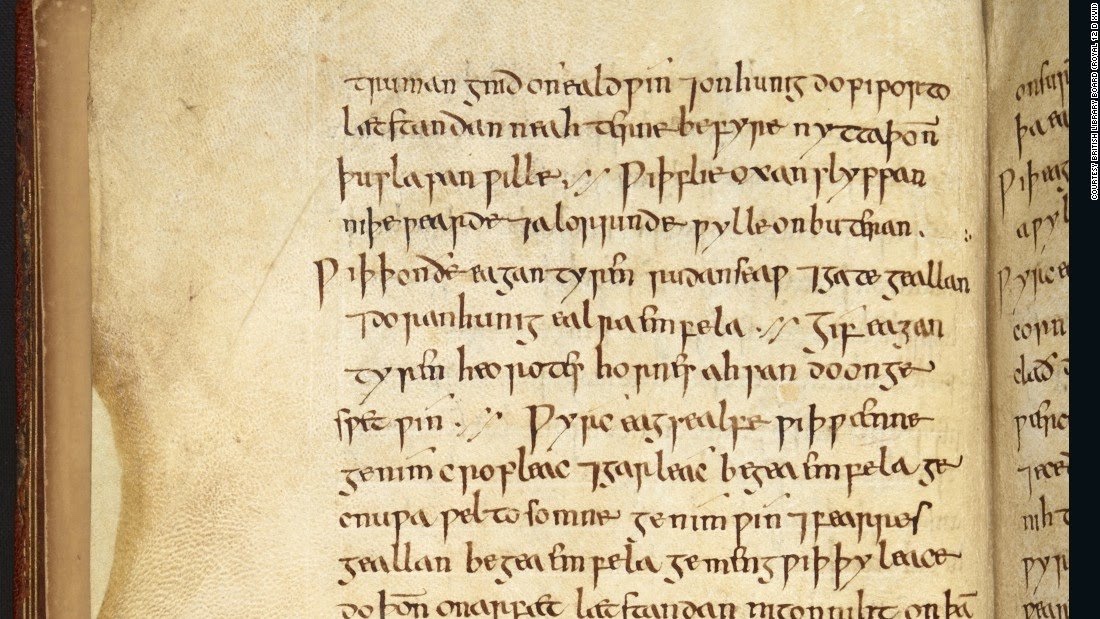

Ralph of Shrewsbury, Bishop of Bath of Well’s, would be similarly pragmatic as he faced a shortage of key workers to hear plague victims’ confessions. In the absence of priests to hear confessions now plague sufferers could confess to each other, or a layman or even to a woman. He commanded this in a letter to his priests written in January 1349:

“The contagious pestilence of the present day, which is spreading far and wide, has left many parish churches and other livings in our diocese without parson or priest to care for their parishioners. Since no priests can be found who are willing, whether out of zeal and devotion or in exchange for a stipend, to take on the pastoral care of these aforesaid places, nor to visit the sick and administer to them the Sacraments of the Church…We, therefore, wishing, as is our duty, to provide for the salvation of souls and to bring back from their paths of error those who have wandered, do strictly enjoin and command..that, either yourselves or through some other person you should at once publicly command and persuade all men, in particular those who are now sick or should fall sick in the future, that, if they are on the point of death and cannot secure the services of a priest, then they should make confession to each other, as is permitted in the teaching of the Apostles, whether to a layman or, if no man is present, then even to a woman.”

History doesn’t necessarily repeat herself but she does like to rhyme. It’s hard not to see the Catholic church’s response to the Black Death in a similar vein to how we in the West approached COVID-19: military involvement, new hospitals, volunteer groups, lockdown, furlough etc.

Two years into the pandemic and many of us might well be questioning our governments and leaders: Boris Johnson’s behaviour during lockdown will probably define his career forever.

In the Middle Ages it was the same. After the Black Death passed there was a shortage of labour leading to the Peasants Revolt of 1381. It could be argued that the Catholic church could never again demand the total power it had once wielded: they had not been able to save people. Questions could be asked and their authority challenged. Within 200 years Lutheranism would rise and Henry VIII would break from Rome. As Europe began to recover the seeds of new discovery had been sown. The Renaissance would see a new era of art and discovery.