Before we conduct any research we first need to construct a research question. This can be a difficult step. Our question needs to be precise and easy to understand. To do this we can use the ‘PICO’ criteria:

Population

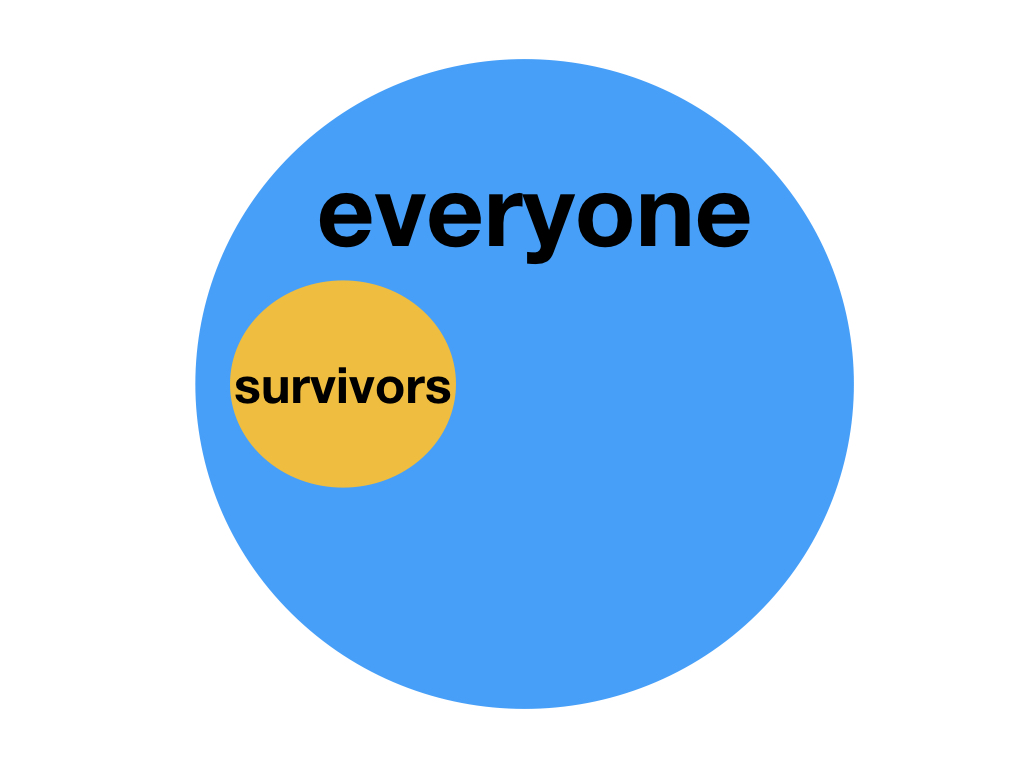

We need a population of interest. These will be subjects who share particular demographics and needs to be clearly documented.

Intervention

The intervention is something you’re going to do to your population. This could be treatment or education or an exposure such as asbestos. The effect of the intervention is what you’re interested in.

Control/Comparison

If we’re going to study an intervention we need to compare it. We can use people without the exposure (control) or compare the treatment to another or placebo.

Outcome

The outcome is essentially what we are going to measure in our study. This could be mortality, it could be an observation such as blood pressure or a statistic such as length of stay in hospital. Whatever it is we need be very clear that this our main outcome, otherwise known as our primary outcome. The outcome decides our sample size so has be explicit.

PICO therefore allows us to form a research question.

To demonstrate this let’s look at the first ever clinical trial and see how we use PICO to write a research question.

It’s the 18th century. An age of empires, war and exploration. Britain, an island nation in competition with its neighbours for hegemony, relies heavily on her navy as the basis of her expansion and conquest. This is the time of Rule Britannia. Yet Britain, as with all sea going nations, was riddled with one scourge amongst its sailors: scurvy.

Scurvy is a disease caused by a lack of Vitamin C. Vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, is essential in the body to help catalyse a variety of different functions including making collagen, a protein which forms the building blocks of connective tissue, and wound healing. A lack of Vitamin C therefore causes a breakdown of connective tissue as well as impaired healing; this is scurvy, a disease marked by skin changes, bleeding, loss of teeth and lethargy. Hardly the state you want your military to be when you’re trying to rule the waves.

James Lind was born in Edinburgh in 1716. In 1731, he registered as an apprentice at the College of Surgeons in Edinburgh and in 1739 became a surgeon's mate, seeing service in the Mediterranean, Guinea and the West Indies, as well as the English Channel. In 1747, whilst serving on HMS Salisbury he decided to study scurvy and a potential cure.

James Lind 1716-1794

Lind, as with medical opinion at the time, believed that scurvy was caused by a lack of acid in the body which made the body rot or putrefy. He therefore sought to treat sailors suffering with scurvy with a variety of acidic substances to see which was the best treatment. He took 12 sailors with scurvy and divided them into six pairs. One pair were given cider on top of their normal rations, another sea water, another vinegar, another sulphuric acid, another a mix of spicy paste and barley with another pair receiving two oranges and one lemon (citrus fruits containing citric acid).

Although they ran out of fruit after five days by that point one of the pair receiving citrus fruits had returned to active duty whilst the other was nearly recovered. Lind published his findings in his 1753 work, A treatise on scurvy. Despite this outcome Lind himself and the wider medical community did not recommend citrus fruits to be given to sailors. This was partly due to the impossibility of keeping fresh fruit on a long voyage and the belief that other easier to store acids could cure the disease. Lind recommended a condensed juice called ‘rob’ which was made by boiling fruit juice. Boiling destroys vitamin C and so subsequent research using ‘rob’ showed no benefit. Captain James Cook managed to circumnavigate the globe without any loss of life to scurvy. This is likely due to his regular replenishment of fresh food along the way as well as the rations of sauerkraut he provided.

It wasn’t until 1794, the year that Lind died, that senior officers on board the HMS Suffolk overruled the medical establishment and insisted on lemon juice being provided on their twenty three week voyage to India to mix with the sailors’ grog. The lemon juice worked. The organisation responsible for the health of the Navy, the Sick and Hurt Board, recommended that lemon juice be included on all voyages in the future.

Although his initial assumption was wrong, that scurvy was due to a lack of acid and it was the acidic quality of citrus fruits that was the solution, James Lind had performed what is now recognised as the world’s first clinical trial. Using PICO we can construct Lind’s research question.

Population

Sailors in the Royal Navy with scurvy

Intervention

Giving sailors citrus fruits on top of their normal rations

Comparison

Seawater, vinegar, spicy paste and barley water, sulphuric acid and cider

Outcome

Patient recovering from scurvy to return to active duty

So James Lind’s research question would be:

Are citrus fruits better than seawater, vinegar, spicy paste and barley water, sulphuric acid and cider at treating sailors in the Royal Navy with scurvy so they can recover and return to active duty?

After HMS Suffolk arrived in India without scurvy the Naval establishment began to give citrus fruits in the form of juice to all sailors. This arguably helped swing superiority the way of the British as health amongst sailors improved. It became common for citrus fruits to be planted across Empires by the Imperial countries in order to help their ships stop off and replenish. The British planted a particularly large stock in Hawaii. Whilst lemon juice was originally used the British soon switched to lime juice. Hence the nickname, ‘limey’.

A factor which had made the cause of scurvy hard to find was the fact that most animals can actually make their own Vitamin C, unlike humans, and so don’t get scurvy. A team in 1907 was studying beriberi, a disease caused by the lack of Thiamine (Vitamin B1), in sailors by giving guinea pigs their diet of grains. Guinea pigs by chance also don’t synthesise Vitamin C and so the team were surprised when rather then develop beriberi they developed scurvy. In 1912 Vitamin C was identified. In 1928 it was isolated and by 1933 it was being synthesised. It was given the name ascorbic (against scurvy) acid.

James Lind didn’t know it but he had effectively invented the clinical trial. He had a hunch. He tested it against comparisons. He had a clear outcome. As rudimentary as it was this is still the model we use today. Whenever we come up with a research question we are following the tradition of a ship’s surgeon and his citrus fruit.

Thanks for reading.

- Jamie