Third year medical students at the University of Nottingham on clinical attachment at the Queens Medical Centre spend one week with us in DREEAM and the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine can be daunting for experienced students let alone those right at the beginning of the clinical phase of the course. Also, as students arrive in the spring their week is often shortened due to Bank Holidays and other commitments such as core teaching. I wanted to find a way to give the students as much information as possible about the working of the department and its protocols as well as a way of increasing contact time to make the most of their attachment. A smartphone application seemed a practical solution.

IT’S EASY

The thought of creating an application might bring to mind Matrix-style screens of numbers and formulas indecipherable to anyone except hackers and programmers. The truth is it has never been easier to create your own application thanks to a number of websites which require no coding experience. A simple Google search reveals just what a crowded market the app building industry has become so I recommend a bit of research to find the platform that works best for you. Most of them work along the lines of choosing a template and then picking functionality such as social media links to add literally in a ‘drag and drop’ style. I chose AppMakr due to its ease of use and because the app also works as a website allowing students to access it on their computers and laptops as well.

The whole process is based on simply picking what functionality you want (say a calendar) and dragging it across. Each function is based on an RSS feed so you link your calendar to a Google calendar or your podcast icon to a SoundCloud feed. In order for the app to have our department’s Initial Assessment Tools (IATs) I created a Google Drive folder containing the guidelines as PDF files and used the shareable link. This meant clicking on the IATs button opened the IATs up for the students to use.

Backgrounds can be played around with. I tried importing pictures but found the resolution and sizes difficult; I think this had more to do with the images I was trying to bring in rather than the website itself.

You can pay to create your app and submit it to iTunes for consideration (it will need to be very good to get approved) or AppMakr will create a mobile website for free. The mobile website for this application can be found here. All students need to do is set the website to the home screen of their mobile or tablet and there, instant application. It was that simple.

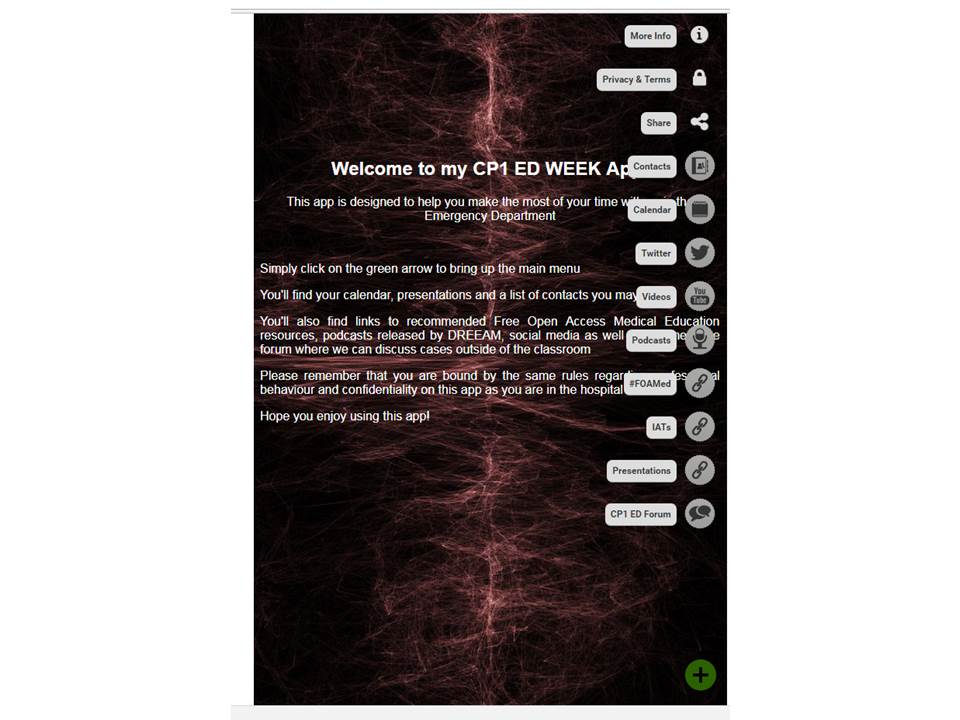

Simply pressing on the green cross brings up the list of functions. The green cross acts as a kind of home button.

Using Google Drive links the presentation buttons bring up the slides for each session. The IATs function works the same. The calendar links to a Google Calendar account created especially for this application.

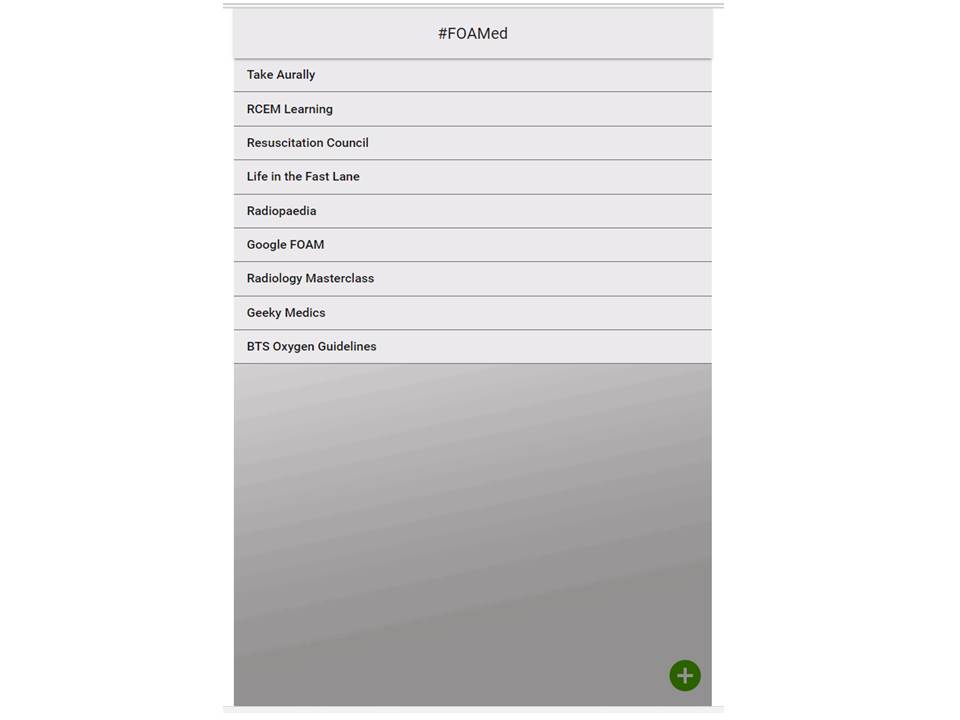

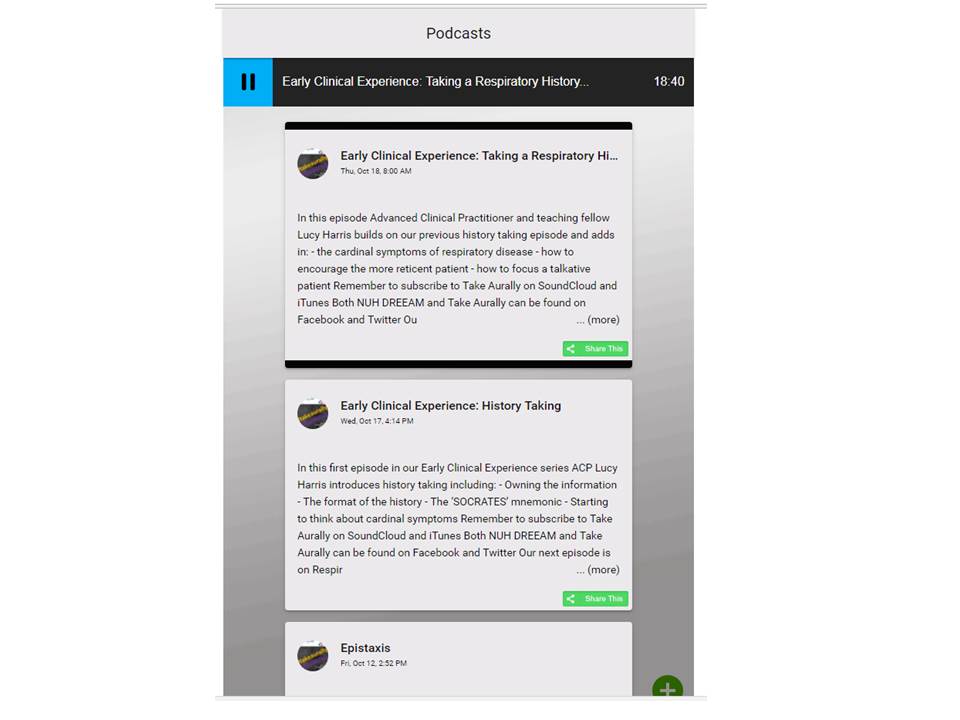

External resources were linked to the application as well. Certain Free Open Access Medical Education (FOAM) resources were linked as well as dedicated Social Media, Podcast and YouTube resources to help the students during the attachment. Unlike other apps this worked without internet connection which helps in the concrete basement of our Emergency Department!

Finally, a forum was created into which students and educators could log in and communicate. This helped share resources and further discussions. This brings me on to my next point:

FLIPS THE CLASSROOM AND BLENDS YOUR CURRICULUM

The flipped classroom describes students being given learning resources before a teaching session. The teaching session is then used to explore the material in greater detail (Heacademy.ac.uk, 2018). The role of the teacher in the flipped classroom has been described as a facilitator and coach or ‘guide on the side’ (Baker 2000). This notion resonates within suggested theories in medical education regarding the exponential growth as well as the shortening half life of knowledge such as connectivism (Siemens 2005) or navigationism (Brown 2006). The growth of Web 2.0 resources such as blogs and podcasts further facilitates this.

Using the application it was possible via the forum and word of mouth to point the students to a particular resource (say a podcast on Abdominal Pain) and advise them to listen to it before their session on Abdominal Pain. By flipping the classroom we can establish a set level of prior knowledge the traditional session can then build on. This maximises the time together. There’s a number of resources aimed at helping educators set up a flipped classroom programme such as this one from the Flipped Learning Network.

The forum allowed further discussions around cases (anonymised) or other subjects that couldn’t be covered in the timetabled sessions. These discussions were held between 1700-1900 in the evening and all students were encouraged to participate. This use of online resources alongside traditional sessions is called blended learning (Heacademy.ac.uk, 2018). The point was that the sessions would lead onto online discussion which would then be referred back to in the next face-to-face session which takes some time to get used to but is rewarding. The Higher Education Academy has a great page on blended learning here.

REAL LIFE PRACTICE IN SIMULATION

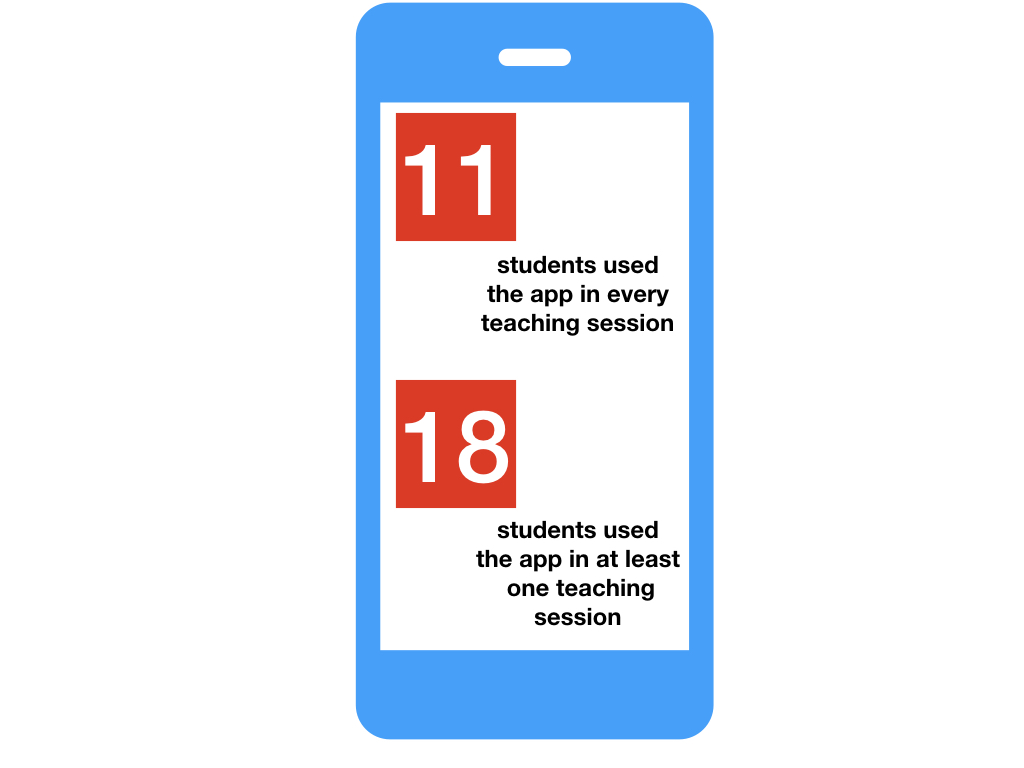

In all 18 students ‘downloaded’ the application. There was an orientation session at the beginning as well as clear guidance on professional online behaviour; so called ‘netiquette’ (Webroot.com, 2018).

All sessions were designed to integrate the application either through guideline reference in simulation or signposted online resources during seminar sessions. All students used the application in at least one session with 11 students (61%) using the application in every session.

The forum transcription was analysed for any emergent themes. As I already discussed the forum was a key part of the ‘flipped classroom’ and improving communication before educators and students. This resulted in logistical messages communicating session changes or short term information such as interesting patients:

There was signposting to resources to consolidate sessions or for prior learning before teaching:

There were also online discussions instigated around investigations or clinical questions:

The reason(s) for students using the application during simulation was assessed. By far and away the most common reason was to look up departmental guidelines (13) followed by looking up national guidelines (4), looking up free open access resources (2) and to look back on a presentation (1).

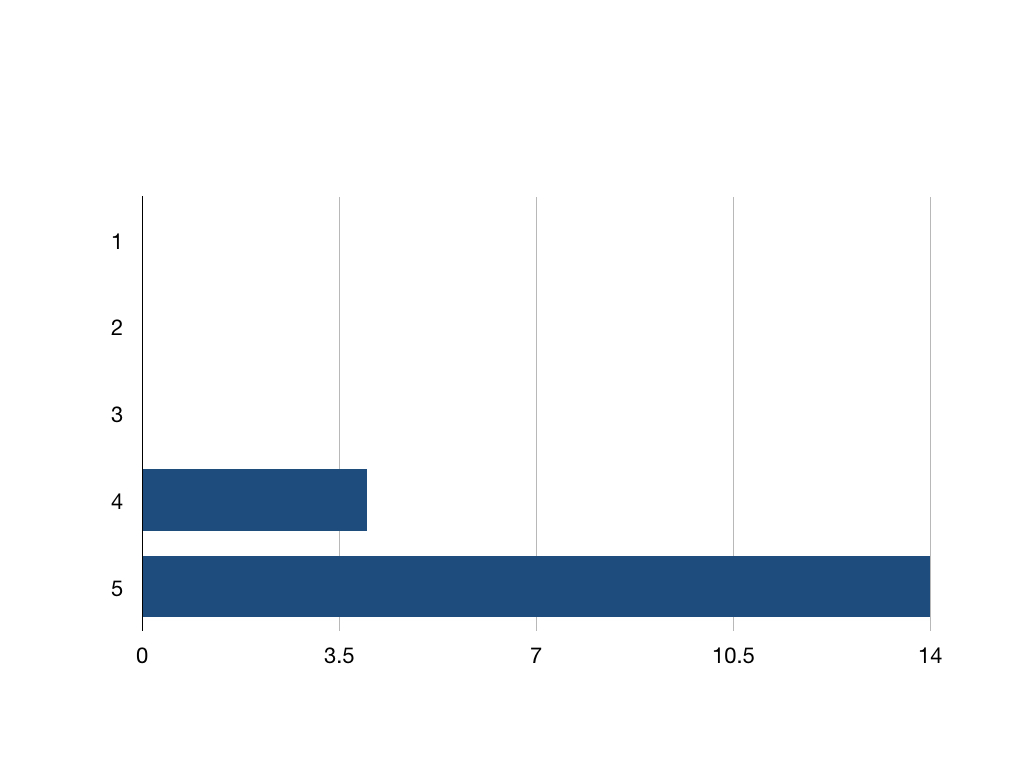

Students were asked to rate the application on a Likert scale. All students rated the application positively (4 or 5) with 14 (78%) rating the application 5/5.

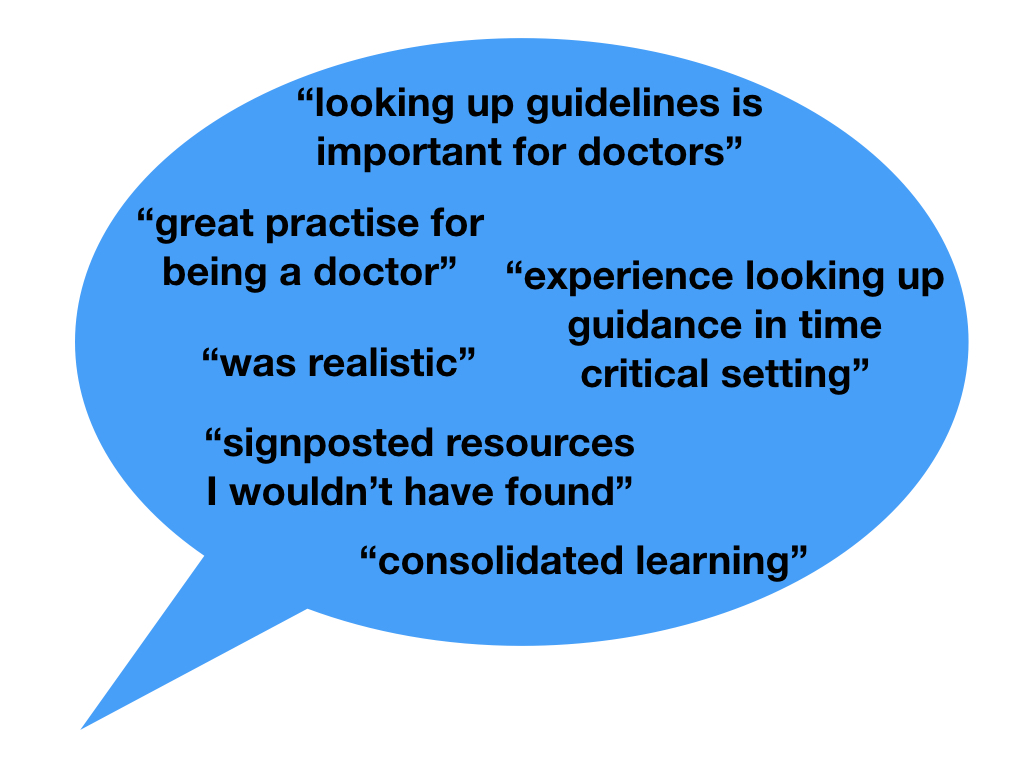

Finally, students were given a free text box for further feedback. As the diagram below shows this feedback focused on themes of reference and reflecting real life practice:

This suggests that medical students appreciate the role of guidelines and technology in clinical practice. The importance of digital literacy and navigating resources for expedient care is well documented with the Royal College of Nursing and Health Education England launching programmes to improve and formalise skills in this area (The Royal College of Nursing, 2018 and Health Education England, 2018). Studies have looked at promoting digital literacy amongst medical students (Mesko, Győrffy and Kollár, 2015). Perhaps with the rise of connectivism and/or navigationism as a learning paradigm we will see even more work into this area with digital literacy becoming a key skill alongside clinical acumen. Anecdotally speaking to the students the biggest barrier to using the application was familiarity. Once this was overcome they felt comfortable using it and contributing on the forum.

Students value innovation from educators but this requires careful design of the curriculum and resources to ensure feasibility and compatibility. The project suggests that application design is feasible for educators with limited coding experience and the results indicate that students engage well with a blended curriculum. Engagement with the application was related to student confidence and perceived relevance. Mobile learning tailored with simulation offers students a realistic experience. Resource design may become a crucial part of educator development. Students require guidance with new resources when presented to them.

Reference

Baker, J. W. (2000) The “Classroom Flip”: Using Web Course Management Tools to Become the Guide on the Side. In: the 11th International Conference on College Teaching and Learning: Jacksonville, Florida.

Brown, T. (2006) "Beyond constructivism: navigationism in the knowledge era", On the Horizon, Vol. 14 Issue: 3, pp.108-120, https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120610690681

Flipped Learning Network (FLN). (2014) The Four Pillars of F-L-I-P™

Heacademy.ac.uk. (2018). Blended learning | Higher Education Academy. [online] Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/blended-learning-0 [Accessed 19 Oct. 2018].

Heacademy.ac.uk. (2018). Flipped learning | Higher Education Academy. [online] Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/flipped-learning-0 [Accessed 19 Oct. 2018].

Health Education England. (2018). Digital literacy. [online] Available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/digital-literacy [Accessed 29 Oct. 2018].

Mesko, B., Győrffy, Z. and Kollár, J. (2015). Digital Literacy in the Medical Curriculum: A Course With Social Media Tools and Gamification. JMIR Medical Education, 1(2), p.e6.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age.International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1), 3-10.

The Royal College of Nursing. (2018). Improving Digital Literacy | Royal College of Nursing. [online] Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-006129 [Accessed 29 Oct. 2018].

Webroot.com. (2018). What is Netiquette? A Guide to Online. [online] Available at: https://www.webroot.com/hk/en/resources/tips-articles/netiquette-and-online-ethics-what-are-they [Accessed 29 Oct. 2018].