Clustering and Horizontalisation

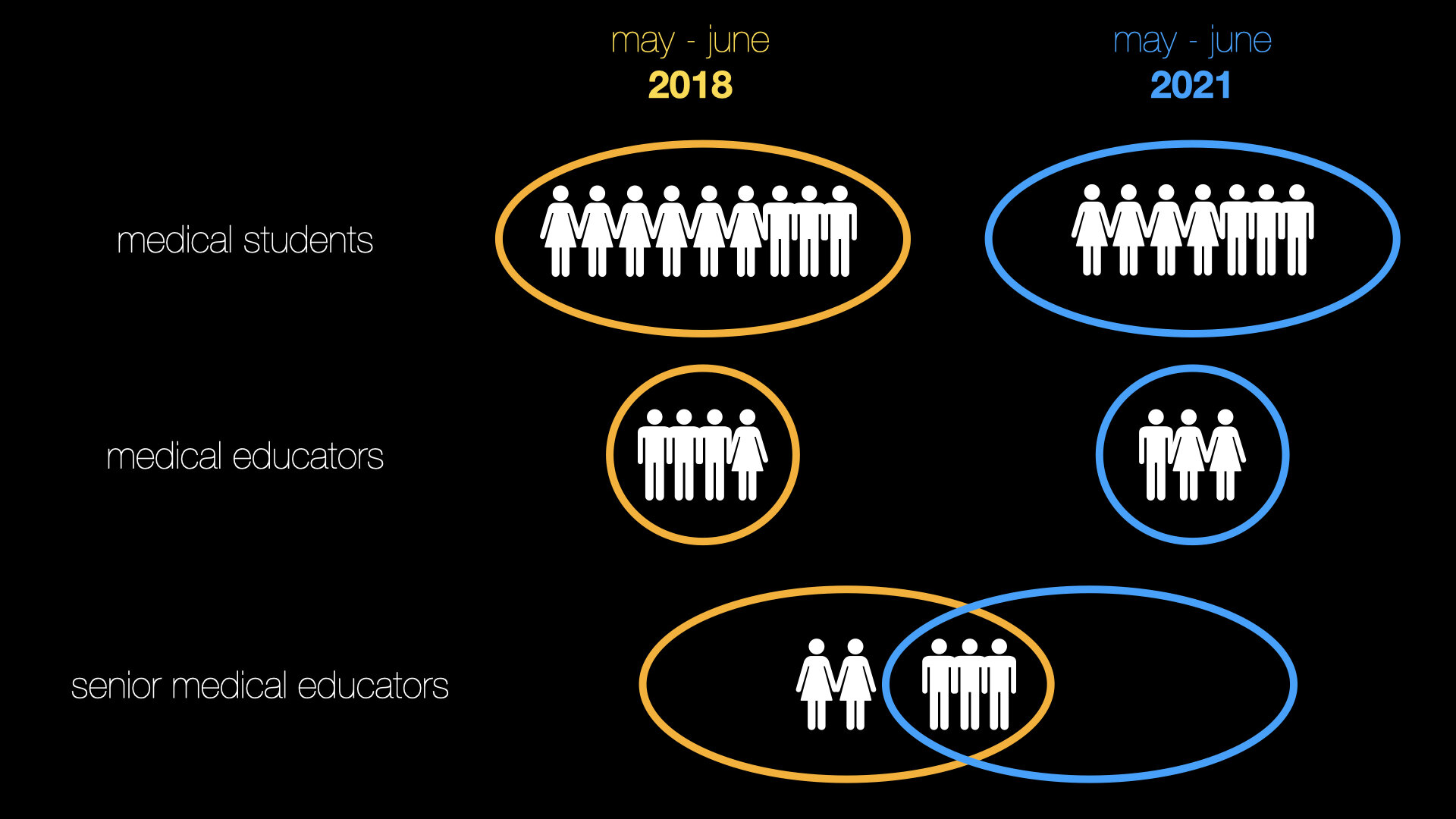

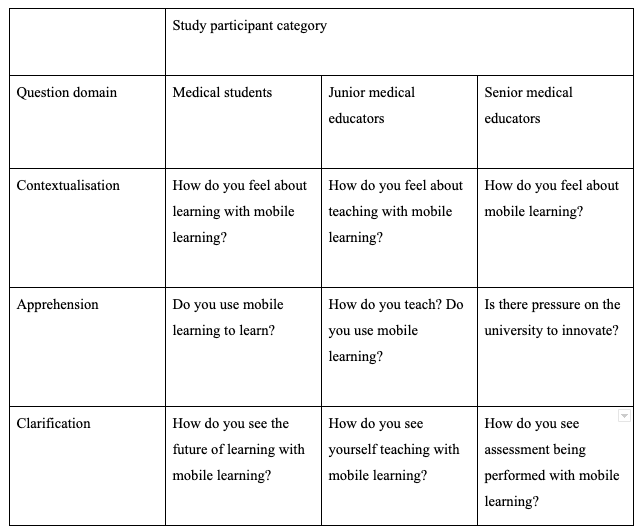

Clustering was performed based on themes in the literature and which may have emerged during the course of the interviews. Based on this horizontalisation was performed extracting the invariant constituents for each participant. All invariant constituents were then used to form the textual description for each participant. The textual descriptions for each participant were used to form the composite description for each participant group; medical student, medical educator and senior educator.

There were six key themes explored amongst the participants’ invariant constituents based on themes in the literature review as well as voids in the research being examined by this study. These were:

Factors influencing students’ use and perception of mobile learning

Factors influencing educators’ use and perception of mobile learning

Participants’ perceptions of social media in medical education

Digital literacy and experience with mobile learning in clinical practice

Experience with collaborative mobile learning

Potential of student engagement with mobile resource design

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of mobile learning (for second round only)

Early on in the analysis process it became apparent that there were a number of emergent themes across the transcriptions. These were:

Mobile learning as perceived as a field of pedagogy

The future of medical education

Assessment with mobile resources

During horizontalisation the key invariant constituents which were felt by the author to capture the essence of the phenomenon being studied (Moustakas, 1994) were included in the composite descriptions so to allow greater reflection of the life experience of participants. The composite descriptions are presented with headings for these emergent themes and their key invariant constituents.

Composite Descriptions: First Round

Medical Students

Perception of mobile learning

All of the students considered themselves positive toward mobile learning to varying degrees. Students felt mobile learning served as a supplement to more traditional teaching.

Medical Student C

“I think it's something that you'd use to supplement your learning, not something that you'd use independently to sort of teach yourself from scratch”

There was agreement amongst the students that they would not engage as well with mobile learning as with more traditional learning and anticipated issues with discipline and motivation.

Medical Student F

“Personally I could do with like a teacher stood behind me like whipping me to get me to work.”

Factors influencing use of mobile resources and experience of collaboration

Recommendation either from a medical educator or a peer was needed before the students would use mobile learning resources.

Medical Student B

“ it's pretty much recommendation for me it's like what I've heard from others are good I just used those ones I don't particularly sort of go around looking for new information I just use what's told”

Only one student mentioned themselves recommending a resource to other students. No student had used mobile learning for collaboration with other students, however, they did see the potential to use mobile learning for collaboration. There was a preference for face-to-face contact with educators and other students.

Medical Student C

“I don't think the platforms I've seen truly compare with just like being sat around a table with someone”

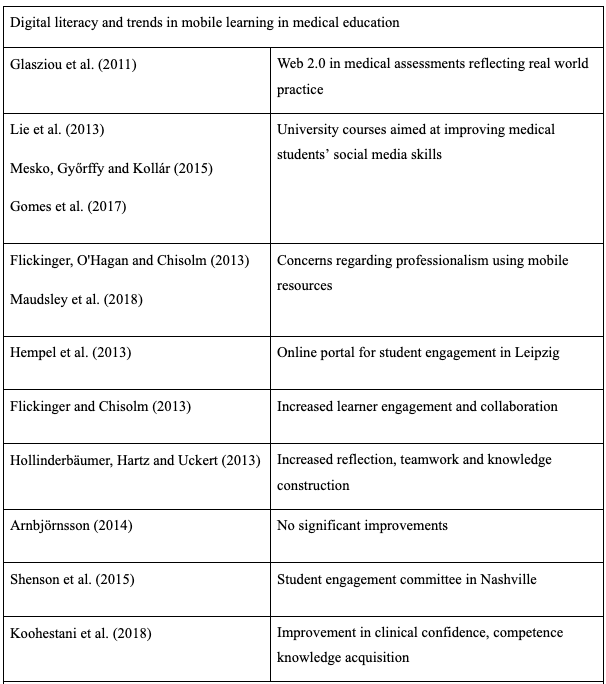

Digital literacy

Students agreed that digital literacy was an important skill for doctors. Students had seen mobile resources and devices being used clinically by doctors of different grades. This helped their confidence when it came to using the same resources and devices. There had previously been an assumption that using a smartphone in a clinical environment would be unprofessional. Two of the students mentioned smartphones being banned at their school.

Mobile resources and stage of medical school

It was felt that the clinical phase of the course provided motivation to use mobile resources due to an urge to seek out extra information to avoid negative consequences such as falling behind in knowledge. As a result it was felt that mobile resources are best used in the clinical phase and would be too advanced for the pre-clinical years. Students were also concerned about more junior learners being anxious without more traditional learning.

Medical Student I

“I think the one difficulty with online resources is that they are sometimes designed for people at a much higher level than we are. So I think even now sometimes using them I can feel a bit overwhelmed”

They voiced concern regarding objectives and other expected standards which contact time seemed to assuage. It was felt that mobile learning in comparison might increase anxiety unless standards were explicit or even demonstrated, such as with a video.

Medical Student I

“I think a really helpful thing would be some kind of consensus on clinical skills”

Current use of mobile learning

There was a difference in the students between those who felt they had used more mobile resources since starting CP1 and those who were using fewer. Those who were using more pointed to the opportunistic and practical nature of mobile resources.

Medical Student G

“it's really easy to find things using your phone basically and it everything has to be accurate so you can just take out your phone and like search up NICE guidelines”

Those who were using fewer did so because there were recommended textbooks for the course they were using instead. However, it was noticed that some students described using their smartphone in a clinical environment but did not consider this as mobile learning as they were in the environment at the time.

Medical Student D

“it's been a lot more focused on being on the wards and just trying to respond to what you find there and that necessarily is something that has to be done in person. Not at a distance.”

Some students did search for mobile resources such as smartphone applications for revision. However, use was short lived due to a variety of reasons such as being from the USA or poor usability. Consistent use of resources was linked to recommendations from educators and repeated use during teaching sessions. The BNF application being used during Therapeutics sessions was mentioned by several students as an example of this.

Perceptions of social media in medical education

Discipline was also considered to be an issue in using social media for education. Students were generally against using social media in education. It was felt that any mobile resources would require oversight and facilitation from medical educators.

Medical Student G

“I can't really imagine using social media for educational purposes”

University mobile resources and access to technology

Students felt competent in their skills using mobile resources and accepted that there was an assumption from the university that they would be able to use mobile technology adequately. All agreed that digital literacy was an important skill for doctors but it was also felt skills didn’t need to be too advanced and one student had observed a ward round being held up due to technical issues. One student with prior experience with mobile resources was disappointed in the quality of resources he’d seen in the clinical setting.

Medical Student D

“coming into this world I was absolutely amazed by how primitive a lot of it is”

Another student said her non-medical friends had been surprised at the degree to which she could progress on her course via online learning rather than through direct contact.

Medical Student A

“friends and family they were a little pretty shocked that...could've actually just do University from a bedroom just listening for them online if you wanted to. “

They were negative regarding university mobile technology in particular about correct information and reliability. Students felt any future resources would have the same technical issues.

Medical Student G

“I’d just be genuinely surprised if the university managed to put out an app that actually worked”

However, it was felt that the university and educators should be creating resources. Standardised clinical examination examples were seen as one area where resources would be very useful.

Medical Student B

“the university should definitely be doing more apps and so guides and things I think are clinical skills teaching in first and second year was a bit hit and miss so that other universities have for YouTube videos with exactly what they want online. So you could watch them and know exactly what you need to do but here it's sort of like here's a checklist.”

It was felt that mobile learning and e-Learning both aided uniform learning across different sites and helped create a universal experience. It was felt that in order for students to fully utilise any mobile resources the university would have to consider equipment and previous experience of a lack of support in this area was reported. No student suggested or mentioned being consulted by the university prior to any new resources being released.

None of the students valued university innovation as a consideration during applying and instead looked at reputation, course design and the pass rate. One student felt that there needed to be a session on available mobile learning resources at the start of CP1 induction. It was felt that the university needed to be better at signposting resources.

Reliance on mobile devices

There was agreement that basic knowledge is needed as a doctor but beyond that further information could be accessed as needed and this was a skill that needs to be taught. However, there was concern about becoming too reliant on technology.

Medical Student A

“if you can't function without having something in your hand like a phone then that's not really going to be sustainable long term”

Medical Student G

“ why do I need to remember the order of drugs to give for like hypertension when I can just search it up?”

Design of learning session based on mobile learning

It was argued that any course based on mobile learning would not be radically different from other teachings that the students had experienced in particular Anatomy in the pre-clinical years and Pathology and Therapeutics in CP1. In Anatomy and Pathology, there is central teaching with extra resources for self-directed learning. Some students felt this model encouraged them to learn whilst others felt they did not have the motivation to make the most of opportunities in this way but still saw the value in it. In Therapeutics, the sessions are based on problem-solving and using the British National Formulary (BNF) application to access information relevant to the case being discussed. These sessions were mentioned in particular as a reason why students had accessed mobile resources.

One student had experienced the flipped classroom at school and felt there was a similarity. Students were mixed in their support for the flipped classroom. This was linked with trepidation regarding discipline and motivation of self-directed use of mobile resources in general. However, it was felt that mobile resources might allow closer oversight of progress.

Medical Student A

“it's just a risk of it all becoming too much online and just, yeah need some kind of interaction at the end of the day like you need to be able to talk to a patient”

Medical Student D

“I certainly don't trust myself... going more mobile doesn’t necessarily less oversight and potentially, possibly an earlier lighting up issues.”

Medical Student F

“the sessions that I take most away from are the ones that I've...I've done all the further reading before.“

Students felt adopting mobile learning was an acceptance of social trends regarding smartphones and other mobile technology. Students saw it being used in simulation and clinical decision making or to look at cases before then discussing findings in a traditional classroom setting. Formative assessment was also suggested. It was felt it would be too overwhelming in the pre-clinical course and would work best in small groups.

In appraising online resources some students did use skills taught to them as part of their course. Others used common sense and chose resources by reputation. Students did use resources not approved by the university such as Wikipedia but as a starting point and not as their only resource.

Medical Educators

Mobile resources in clinical practice and in teaching

All of the medical educators used either online or mobile resources as part of their clinical practice for quick reference. The majority (three) of the medical educators used mobile resources as part of their teaching either in a classroom or ward based environment. They mentioned that this reflects real life practice and prepares students for working as a doctor. Their attitude towards mobile learning was predicated on their own use.

Medical Educator A

“anything I’ve used or had experience of I would recommend and I found easy to use, yeah I’ll just recommend to people”

One educator discourages the use of mobile devices in her sessions.

Medical Educator D

“in the classroom, I have to say I'm not a massive fan of mobile phones because I see students on Facebook, Instagram and texting...I do think that it ultimately does distract you from what is going on in front of you”

Educators who didn’t regularly teach using mobile learning described themselves as “old fashioned” in their outlook.

Medical Educator C

“So I would probably say I'm a bit more old-fashioned...I'm still probably more a textbook kind of person”

Medical Educator D

“So, I think I'm probably bit old-fashioned in that no not really I know that some of my other colleagues at induction will recommend certain apps and things and I have to say that I don't. And that's because I don't use them myself”

Practicality, the amount of knowledge available and the rate of change were also factors in choosing to use these resources in both teaching and clinical work.

Medical Educator B

“I think the best way to learn to use technology is often by necessity”

Factors influencing the use of mobile resources in teaching

Mobile resources were recommended if they had been used in the educator’s own clinical work and so were trusted and from a validated source. The mobile resources mentioned were published from renowned books or websites that predated them.

Medical Educator B

“I tell them to download the BNF on the first day of placement...the reason I recommend those apps is because I use them as a junior doctor and they need to get comfortable using those different modalities of accessing information”

The medical educator who didn’t recommend mobile resources did so because she didn’t use them in her own practice rather than for an educational reason. One medical educator believes that without technology doctors will struggle to stay relevant.

Medical Educator C

“I've seen the most senior consultants pull out their smartphones and use it for very specific things. Research changes so quickly...the ones that are slow to change others ones that are slow to stay relevant”

There was a discussion about how mobile learning was impacting students’ relationships with knowledge.

Medical Educator B

“I think a lot of the students take a lot of knowledge for granted and knowledge is a bit more

disposable...how you get the information becomes the key cornerstone of it rather than the actual information itself.”

Medical Educator C

“think there are some limitations in it that some students would be reluctant to get too deep into the actual knowledge...”

Digital literacy and designing teaching based on mobile learning

All of the medical educators agreed that digital literacy is a key skill for doctors and that access to and proficiency with mobile technology were expected in medical students.

Medical Educator B

“we’d be doing our students a disservice if we didn’t improve their computer literacy as well”

It was mentioned that support is needed for medical educators to produce their own resources. Three of the medical educators had experienced issues with using mobile technology in their teaching, mentioning Wifi failure and difficulties with information governance as reasons sessions hadn’t gone as planned.

One medical educator felt unsupported by the university when trying to set up a new teaching programme based on mobile learning as they wanted something more tangible and traditional. One of the medical educators always has a backup plan when a session using technology is planned due to a fear of issues arising.

Social media in medical education

One of the medical educators was enthusiastic about using social media in education as the best way to keep up with developments in Medicine.

Medical Educator A

“Yeah I think it’s a good thing…because advances in medicine and things are changing sorted so rapidly, it seems to be really the best way to sort of keep up with those advancements”

Other medical educators were hesitant. It was believed that social media posed the challenge of students being able to vet the information they find. It was felt that this is not a skill taught well to students. There was agreement in doctors having some form of social media presence and using it to share information. The risks of professional behaviour and public image were mentioned, with social media activity as a student having potential repercussions even when graduated. However, the use of social media as a community was mentioned as a benefit.

Medical Educator D

“I have very mixed feelings about social media in general, in terms of our lives as doctors. Because I think we are, whatever you put out is exposing you to a certain amount of risk..I do think it's a valuable resource and the other thing that I suppose that Twitter specifically gives you is a sort of a sense of community as well. And medical school can be incredibly isolating, it can be very lonely sometimes.”

One medical educator surmised that that educational and research in the future might change as a result of students now being so accustomed to and experienced with social media.

Medical Educator C

“the question will come in about five or ten or fifteen years’ time when the people of this current age other people that are making their decisions. When they're consultants and they're the ones that's putting out information are they then going to be susceptible to was kind of sensationalism to get the message out and cut corners on research or discussion or context”

Collaboration using mobile learning

One medical educator was concerned about him and his colleagues working in silos and needing to collaborate further. Although there was agreement about using mobile learning to access up to date information there were no further comments about sharing information across mobile resources.

Medical Educator B

“I think if we are to innovate, we need to have a more networked approach between the different educational providers...we’re replicating the same work that’s being done in multiple different hospitals open around the world”

Role of the educator and mobile learning

All of the medical educators saw themselves in some kind of guide or signposting role when they teach.

Medical Educator D

“I'm very much there to kind of guide”

All emphasised that they are not the source of all information. They all bring their own clinical experience to teaching emphasising the nuances and differences from a theory that can happen in real life. This came out as one of their perceived strengths of the teaching fellow role. These nuances were felt to be important to clinical medical education. One medical educator felt that the traditional teacher role didn’t suit modern Medicine.

Medical Educator C

“I think because actually the unique role that our current role as clinical educators is that we are more, we are closer to them from a teacher learner role than a traditional classroom environment teacher learner role. Whereby they would always look up to the teacher and expect them to know everything , that’s not what Medicine is and again that rose back to what we how we practice clinically”

Perceptions of mobile learning

Reaction to educators focusing on mobile technology was mixed. One medical educator felt teaching through mobile learning wasn’t vastly different from situated learning or social learning theory whilst another felt it sounded like PBL.

Medical Educator B

“situated learning and potentially social learning theory, because we’re using technology to

communicate between people. It's just changing the format of the communication. And then

situational learning we’re just placing the learning activity in a different situation with different technology. But it’s still an information exchange, it just happens since before educational theory were invented”

Medical Educator D

“certainly my understanding of PBL is that you're given a problem and you're asked to solve it and you're shown potentially where you might look for that information. So on the face of it sounds very similar”

There was general agreement that using mobile learning is well established as an educational tool and that it would work best for the more experienced undergraduate students or in the postgraduate sphere.

Medical Educator B

“For junior undergraduate medical students, they’ve not learnt that level of critical appraisal yet. So, getting them to use resources where it’s not all valid and it’s not over liable information becomes a bit of a dodgy situation in my opinion… It’s not something that we explicitly teach very well in undergraduate medicine for, perhaps using technology is a good way to do it.”

The medical educator who doesn’t use mobile resources felt that her normal approach using real life props such as clerking sheets was similar in principle to using mobile learning just without the technology as it focuses on realism.

There were concerns that weaker students might not engage with mobile learning and that it would be harder to keep an eye on student progress. It was felt that mobile learning would require an element of contact time with more traditional teaching to ensure there is a grounding of theoretical knowledge. One medical educator mentioned her own opinions regarding the cost to students of medical education and the expectation of contact time that comes with this.

Medical Educator D

“If I’m paying for something I’d quite like that to be delivered to me.”

Designing teaching sessions based on mobile learning

It was felt that mobile learning would work better in smaller groups of students. Proposed sessions involved simulation to replicate real world practice or in case based discussions looking up guidelines and treatment algorithms. One medical educator suggested running the session similar to PBL.

Medical Educator B

“I think like using a PBL type session, would make a lot of sense”

Another proposed session was similar to the flipped classroom which two of the medical educators had used with good results. One had encountered as a student himself.

Medical Educator A

“I’ve had experience of it as a learner, quite a long time ago and it was very different then...whereas, now because everything sort of is more to hand, I think you’ve got more ability to make it more interesting and more interactive...some sort of interactive learning, after the teaching and then come back and stop discuss that...then feedback on what they’ve found or they could do it through case based discussions or something”

It was agreed that students usually brought correct information to flipped classroom sessions without much direction needed. It was also felt that mobile learning activities would follow a more traditional didactic session and would need to be explained to students as a concept.

Medical Educator C

”would not be the first thing you do, but it may be the third or fourth type of thing you would do. So you would use it to build on top of previous knowledge that you gained from a different aspect or something”

Concerns were voiced about how information could actually be covered in this session with one medical educator feeling it would cover more behavioural activities than knowledge.

Medical Educator C

“I guess you just have to be careful of how much information from a knowledge one of you are going to try and give in this sort of setting….but I guess it would be more from work from a behavioral point of view that I would try and plan a session. And less on hard cold facts trying to get people thinking in a particular way as opposed to these are the set numbers I was you’re able to learn”

No medical educator saw mobile learning as completely or mostly replacing traditional learning exercises. No medical educator suggested involving medical students in the creation of resources.

Senior Educators

Student engagement in designing mobile resources

One senior educator had noticed a push for resources from students and suggested forming a focus group with them.

Senior Educator E

“I think there is certainly a push for more resources. ..But I think you know I think giving them a choice you know I think is something that we wanted, we've had to find you know to find out and do focus groups and stuff”

Perceptions of mobile learning

All of the senior educators had experienced mobile learning in some capacity although only one had actively used it in their lessons with interactivity and pre-course materials. One senior educator was sceptical about mobile learning in general, viewing it as similar to reading a book, albeit easier to seek out information. He felt with technology there was a focus on the novel over their actual value and that mobile learning brought unique challenges due to the unpredictable quality of information available.

Senior Educator C

“learning, is learning, doesn't matter how it's delivered...the fact that it's shiny in technology that makes it seem like it's something special...it brings with it far more problems that any of the other methods because as well as all the good information you've got a lot of dross in there as well”

One senior educator felt her age and preferred approach to learning precluded her from using mobile learning.

Senior Educator D

“No, I'm very old...I would like to have time to be a bit more reflective about it (reading), which is probably why I haven't used it as a learner...But I guess I'm not, you know, I might not be typical and young people might like to do it.”

Role of educator

All of the senior educators agreed that medical education had moved from the more traditional models. There was a general agreement of the role of an educator as either a guide or facilitator.

Senior Educator A

“I do see it very much as a facilitator role rather than a teaching role and I think that something has changed over my period of life as an educator.”

Access to technology

Technological limitations were mentioned as affecting the use of mobile learning; in particular the availability of Wifi. It was felt that modern students all have access to mobile technology and the ability to use it. The University of Nottingham had considered giving students a mobile device as part of their course but this has been rejected in favour of infrastructure investment and it was felt that students would rather use a device they were used to.

Senior Educator C

“I think part of the argument of not doing that is well actually most students have got their own preferred device and better to try and run systems that can actually work”

Although it was argued that it was possible to study Medicine without mobile technology it was noted that the university only had to loan mobile devices to fewer than ten students a year.

Digital literacy

It was mentioned that teaching with technology can often focus on the teaching about the technology itself which one senior educator felt was unnecessary due to the students’ abilities growing up in the mobile era.

Senior Educator B

“kids are doing that all the time they're experts in it.”

Another senior educator felt that current students had been conditioned and protected with modern technology and did not have the experience of his generation with the internet in its earlier imperfect stages and so their technological knowledge was lacking.

Senior Educator D

“we say that students are okay with technology but actually the students who are starting University now aren’t as technically literate as students who were starting five ten years ago…if something goes wrong they don't know how to deal with it...”

Innovation

Innovation was seen as useful with varying degrees of emphasis. It was agreed that branding was still important to the university at least for now, although one senior medical educator felt this would change quickly without innovation.

Senior Educator B

“I think in the short term clearing the branding and the names will stand out but I think if universities are clearly left behind that will become apparent very quickly”

Senior Educator C

“Russell Group universities look better on paper and even with fluctuations in league tables...there's a brand behind the universities”

Two of the senior educators pointed out that innovation does not mean technology alone and pointed to curricula as an area for innovation that students appreciate.

Future of medical education

One senior medical educator went further and argued that Medicine was moving away from being doctor focused into a more generic medical worker from various backgrounds accessing knowledge as needed. He also felt that a number of medical professions may be made redundant due to technology and that universities would become increasingly redundant with more virtual education.

Senior Educator B

“I think in the future the concept of a doctor is a kind of a dead duck...we'll be looking at a kind of a more generic healthcare worker...Radiology as it is now probably won't exist... “

Two of the senior educators admitted they did not know what medical education would look like in the future and this was a challenge to the university and medical education.

Senior Educator C

“(is)a new medical student gonna be prepared to be working in to 2050, which is what they’re going to be doing now, which is very, very scary.”

Collaboration

It was felt that the university does not collaborate as well with other universities as it could do. There was an understanding that branding and intellectual property were important and to forego these would mean missing out on funding.

Senior Educator C

“I was quite frustrated...I can see the other side of it...it would be giving away, you know up to 40 percent of income, if it were to relax its intellectual property rights”

However, it was argued that once students are at university and with the forthcoming GMC Medical Licensing Assessment competition more cooperation may be necessary. Memorandums of understanding were suggested as a way around intellectual property rights.

Senior Educator D

“we shouldn't really be competitive with (other) medical schools...we're after students who are...all pretty much the same...once we've got them do we need to be competitive...we're all moving towards the central licensing examination, so we should all be singing from the same hymn sheet”

Mobile learning as pedagogy

Only one of the senior educators was enthusiastic about mobile learning due to its benefits with individualised learning and wanted it to be embedded more into the curriculum but only if it was blended.

Senior Educator B

“I'm a great supporter of the concept and I think it's got a massive value...it allows for individualised learning in a way that we don't at the moment tailor it to...I think they have to be part of a blended approach”

The other senior educators varied from calling it a “tool” to dismissing it as a “21st-century PBL”.

Senior Educator A

“It’s a tool, one of many”

Senior Educator C

“I think it's just it's just a progression of technology of it is a sort of it is a more up-to-date 21st century PBL really.”

There was agreement that the amount of knowledge and rate of change made retention difficult and necessitated the ability to access information quickly.

Senior Educator C

“the actual sheer amount of knowledge is impossible for any one person to hold”

Senior Educator D

“there's a lot to be said for that approach I agree that really we shouldn't focus on knowledge, delivery of knowledge as much as being able to find the knowledge out for themselves”

Mobile learning in clinical practice

Two of the senior educators noted that they were using mobile learning in their clinical work and felt comfortable with this. There was acceptance of doctors admitting the limits of their knowledge although this may go against the current culture in Medicine.

Senior Educator B

“I think one of the most important things for the medical profession to learn to be able to say is I don't know...goes really against the grain of what its being kind of impaled into them. And that's dangerous for patients”

Senior Educator E

“I will say to them that I just want to check the current guidelines.”

There was discussion about the dangers of being reliant on technology and how useful a doctor with limited knowledge would actually be especially in situations without technology. It was felt that mobile resources are only useful with the foundation knowledge and would need scaffolding with traditional teaching methods.

Senior Educator D

“you can't go orienteering if you don't have to read a compass.”

Senior Educator E

“I think that would be harder if you'll coming in without baseline knowledge...talking about the novice learner...I think that's harder because the more advanced learning will you'll be able to scaffold that information”

Role of mobile learning in medical education

All of the senior educators commented on the importance of communication and interpersonal skills and doubted that these could be taught through mobile learning.

Senior Educator A

“unfortunately that we’re potentially going to miss...one of the things I think people get out of sometimes face-to-face learning as I would class it, is that social interaction as a group. Being there in the room and I don't think whether you could get that (with mobile learning)”

It was argued that students choose optional modules and provide positive feedback based on contact time with educators over other learning opportunities. It was also felt that students are resistant to non-classroom based learning against experiential learning which two of the senior educators felt was the correct model for clinical learning.

Senior Educator C

“experiential learning for Medicine is really important,,,the more you do that you see the nuances and things fall into place and that's I guess that's what our current students are perhaps lacking.”

Senior Educator D

“students are very focused on the fact that they're paying for an educational experience..they’re customers and they want face to face time which shows, you know in their preferences for attachments they would prefer to go to attachment that provides lots and lots of classroom teaching”

One of the senior educators admitted choosing courses based on the amount of social interaction.

Senior Educator A

“I picked the course that had face-to-face learning education rather than one that was solely based on e-learning as their prime resource.”

It was commented that as technology becomes more prevalent there will be increased importance on medical students to learn and provide non-technical skills such as compassion and empathy.

Senior Educator B

“they still need to be able to interact at a human level...to impart all the other elements of healthcare which are around communication, kindness. All of the things to help make people physically and spiritually better.”

The Johari window was mentioned in the context of doubting that students would be able to address all their learning needs using mobile learning.

Senior Educator C

“you don't know what you don't know. Doing that Johari window and you don't know where to look”

There was some feeling that mobile learning would better suit postgraduate students who already have a core knowledge set.

Senior Educator D

“probably more so in the postgraduate sphere where there on any fixed learning objective..the undergraduate course there are boundaries to what we expect them to know and we don't need them to go...when you're in clinical practice anything can present”

Teaching sessions based on mobile learning

Mobile learning teaching sessions were seen as using mobile devices for engagement in larger groups whilst for smaller groups sessions on situation judgement or similar to PBL or the flipped classroom model were suggested.

Senior Educator C

“it's more that's a flipped classroom...go away you know look at this subject and then come and then within the class you'll actually then start to work through to the next level.”

Assessment with mobile learning

When it came to assessment with mobile learning different models were suggested including in work assessment or simulation demonstrating information seeking in a real world setting. Open book knowledge exams were suggested as well. It was argued that such assessments would be add-ons only rather than the main mode of assessment.

Senior Educator E

“assessment is changing all the time and I think we have to align ourselves with the direction of where things are going…”

One senior educator said that mobile learning was not in the university’s plans for future development. It was argued that the GMC would need reassurances from the university that learning had taken place using mobile learning and felt it would be difficult to achieve. An example of compulsory e-Learning modules being left to run in the background was used.

Senior Educator C

“The GMC is a quality assurance body...it would have to have all of the assurances that...your students have actually opened on the message and actually learn it...sometimes you know this compulsory learning...you have a 20 minute podcast... I switch it on sometimes and walk away and make a cup of tea...those sorts of things immediately the GMC quite rightly would not want to endorse”

Social media and medical education

Senior educators were mixed over social media. It was equated positively with professionals talking as though in the doctors’ mess but was also seen as a barrier to social interaction. Social media was equated to Wikipedia as a potential starting point to find information and there was acceptance of using a variety of sources not necessarily from a university for finding information but it was emphasised how important it is to use quality assured sources and facilitate.

Senior Educator A

“I think it's great if it's been peer reviewed”

Senior Educator B

“the best learning is done by people just sitting around chatting...the ability to do that virtually in chat rooms and chat forums and stuff like that is again it's the same thing as a social construct”

Senior Educator C

“you know I get pretty angry if I'm trying to teach a group of students and they're actually twittering at the time...I don’t like it in my gut it annoys me....it comes down to...interpersonal relationship skills that I find that...a bit rude to be honest”

Senior Educator D

“if they're using social media as a jumping-off point to find other thing, then that's absolutely fine. It's no no different than having a chat in the doctor's mess”

It was commented upon that the Trust computers block or limit a lot of social media sites that students might use for clinical knowledge. There was a general agreement that there is no explicit teaching in appraisal skills for medical students. It was hoped they are picked up in their honours year project or through trial and error.

Composite Descriptions: Second Round

Medical Students

Students openly admitted fear and a desire to help during the pandemic.

Medical Student O

“I was obviously worried...my family was worried too...you just want to be safe, for everyone to be safe”

Medical Student P

“I wanted to help, that’s why we want to be doctors, to help”

All students reported using more online resources since the onset of the pandemic. This seemed to be driven by necessity more than any other reason and due to convenience. Some students noticed a change in their approach to finding information themselves or in asking to be signposted by their educators.

Medical Student K

“I’ve definitely used online things more since the pandemic”

Medical Student O

“It's a necessity isn’t it? It can be that or nothing”

Medical Student P

“Needs must”

Medical Student K

“Rather than waiting for something to be given to me I had this time, I was at the computer anyway why not have a look at what there is?”

Medical Student L

“I looked at lots of things...I was asking more for guidance to resources than I would have done before when I wouldn’t ask to be pointed to stuff online”

Students had noticed the amount of fake information being spread especially on social media which had fostered a distrust of the medium.

Medical Student J

“I realised how much rubbish is out there”

Medical Student L

“I think I tried to stay off social media anyway let alone for learning”

Students were mostly negative about the change compared to their previous teaching. There was some discussion regarding the lack of contact time and the perceived lack of value for their tuition fees. One student categorically stated that they would not have gone to a medical school taught virtually. Loneliness and boredom were common experiences. One student, however, had seen some benefits to virtual learning, especially the flexibility it afforded.

Medical Student J

“I think it made me miss face-to-face teaching more”

Medical Student J

“It’s not what I signed up for...obviously this was unprecedented...but...not what I signed up for at medical school at all...I would never be at a medical school run like this”

Medical Student L

“I hope things get back to normal as soon as possible...it’s not really how to be a doctor is it?”

Medical Student K

“I miss my friends. I miss patients and going out to hospital...I’m fed up of my room”

Medical Student O

“It is a lonely way to study...I know it’s all unprecedented but it’s not exactly value for money is it?”

Medical Student P

“I’m not saying I’d want this to carry on forever...but some things are better...like why can’t I learn when I want to?...I’d be sad if we didn’t keep some of the changes”

Medical Educators

The medical educators reported a feeling of confusion at the beginning of the pandemic with face-to-face teaching being cancelled as well as the obligations of being a doctor foremost. They reported needing guidance from the university in adapting their teaching and being safe for students. Once again, a necessity as a driving force was mentioned.

Medical Educator E

“It’s been weird...so weird”

Medical Educator F

“There was a time of just thinking ‘what on Earth can I do?’

Medical Educator G

“I’m a doctor first. So I wanted to be there for patients. I’m sorry but teaching wasn’t my priority”

Medical Educator F

“We needed guidance...like...talking to the university...what do you want from us now?”

Medical Educator G

“I had a timetable and everything arranged and I’d planned my teaching. The next thing I’m being told that it’s all cancelled...was a really disconcerting moment...wondering what the heck to do”

Medical Educator E

“Safety had to be the priority”

Medical Educator E

“There’s that saying about necessity being the mother of invention or something. There was definitely a moment of thinking ‘what can I do?’”

Two of the educators stated that they had been forced to try new things in their teaching as well as creating new learning materials.

Medical Educator F

“It made me try new things. I had never used Teams or made anything for online teaching before”

Medical Educator G

“Definitely a lot of chaos...lot of having to do stuff I had never done before”

Two of the educators had sought the help of other educators in order to meet their teaching obligations.

Medical Educator E

“Principles were the same but still I was asking for help a lot”

Medical Educator G

“I needed help”

All of the medical educators felt that students needed more guidance in the new learning environment than before. There was discussion about students having a responsibility to use the time they had productively as well as whether students could be trusted to find resources themselves.

Medical Educator E

“Students can’t just go to the ward to practise or you can’t just take them to ward so we had to be better at finding stuff and I think students needed a really clear guidance to resources”

Medical Educator F

“There was a moment of saying to students ‘you have this time, use it to find stuff’ but they definitely needed guidance to resources”

Medical Educator G

“Students really can’t identify good stuff”

One medical educator felt that the change in teaching reflected broader changes seen at the clinical level.

Medical Educator G

“There was enough change at the clinical level with distant consultations etc we had to show that change in teaching as well”

However, one educator had concerns regarding pastoral support for students online.

Medical Educator E

“There’s definitely something lacking. In the room you can judge a student’s body language and see if they're struggling. You can’t see that on a screen, even if they had their screen on, or in emails”

Two medical educators were pleased about their experience in making online resources. One felt that all educators would need to make some online materials as a back-up at least while the other felt teaching online was not as good as traditional teaching.

Medical Educator F

“I’d be pleased to go back to ‘normal’ but definitely I think now every educator needs to have some online stuff”

Medical Educator G

“I made online resources and felt proud of that but it didn’t feel anywhere near as good (as face-to-face teaching)”

Senior Medical Educators

In a similar vein to the medical educators, the senior educators recalled the feelings of confusion at the start of the pandemic. There was some discussion about involving students in the changes made and how those changes were communicated. Student safety was again a concern with one senior educator arguing that by keeping students safe there was space to make further decisions later. It was felt that students needed to be patient due to the nature of the disruption.

Senior Educator A

“Student safety has to be the priority. End of”

Senior Educator B

“I think students understood the changes. It’s not as if this was a foreseeable circumstance. We had to explain to students that we were doing the best at all times but the situation was very, very fluid”

Senior Educator C

“Basically...everything was out of the window”

Senior Educator A

“You’d love to include students in this but, ultimately, you have to make decisions and in the beginning it was very much about...being safe, let’s make the safe decision first and let’s go from there”

Senior Educator B

“It’s not great to be totally top-down but what’s the alternative? There’s a deadly pandemic virus on the one hand and on the other a group of young people we have a duty of care for. It’s a no-brainer to say ‘stop it, be safe and we can look at things in the future’”

Senior Educator C

“Obviously students had concerns but I didn’t feel there was anything wrong in saying ‘give us a bit of time here’...it’s not as if we knew this was coming and we had to...build the plane while flying it”

With regard to moving to online teaching, the senior educators acknowledged that there was a lot of disruption. They disagreed about how ready they felt the university was. There was a discussion about how everyone needed to learn how to switch to online working and how to bring the students along.

Senior Educator A

“There was a model which is very tried and tested, this clinical attachment with students learning through time with patients...almost like an apprenticeship...suddenly we can’t use that anymore”

Senior Educator B

“I was in meetings with other doctors where we couldn’t get Zoom to work and I remember feeling worried. I thought everything was going to go wrong”

Senior Educator C

“Luckily we had a virtual learning platform to share information, slides, podcasts etc and so we had some expertise and something to use as a launchpad for more things”

Senior Educator B

“I think it’s something we all got better at...there were tips all over the place about how to use Teams and how to actually have an online meeting...people really needed to learn this stuff and that includes students...can’t just do the same thing online and that’s learning”

Senior Educator C

“You had to acknowledge ‘this is weird’ and set some rules and guidance because students didn’t know how to do it”

There was also a discussion about how assessment was shaped by the pandemic. Not all of these changes were felt to be negative.

Senior Educator A

“Basically we had to say what we couldn’t do and then look at what was left, what we could do...we can’t do exams in person so what can we do online?”

Senior Educator C

“Maybe it showed what is actually necessary. Rather than the ‘nice to have’ we were looking at the essential only...we had online vivas without patients but exploring concepts with students. That was obviously a compromise and not ideal but it took a fraction of time and money...not saying this is the future, like I said it wasn’t ideal but it showed an alternative which had merit”

There was also a discussion regarding the future. It was felt that some degree of virtual communication will remain but that it was impossible to jump to telemedicine without the step of patient contact on the way to gain experience. It was felt that any changes toward virtual medical education will follow changes toward virtual medical practice.

Senior Educator A

“I think we will all want to get back to normal as soon as possible. Maybe in future rather than meet in person we will say ‘let’s chat on the phone’ or on Teams and maybe patients will push for telemedicine as it fits in with them but I think medical education will get back to normal as soon as possible”

Senior Educator B

“I don’t think this is how things will be done. Medical education follows medical practice and so the only way you’ll get it being the future is is medical practice is all virtual”

Senior Educator C

“Patients are the focus of being a doctor and so you’ll always need that patient contact. It’s one thing having the patient contact experience and then moving to virtual consultation but another thing entirely to skip that step...of patient contact...and jump to the virtual”

Summary of findings

This study broadly supports previous literature; that educators do not perceive all mobile resources to be of equal value and are particularly mixed regarding social media. Participants valued contact time and viewed mobile resources as an adjunct, not a replacement, to traditional methods of teaching. There was broad agreement that mobile learning would require a foundation of knowledge best achieved through more traditional learning such as seminars with direct contact. It was suggested as being best used for senior students or in postgraduate education. Suggestions on the best use of mobile learning focused on using it to supplement established teaching or as well signposted stand alone sessions after more traditional learning had taken place. Students did not perceive university resources to be of high value. Educators pointed out that mobile resources are just one example of innovation and may distract from work in other areas such as curriculum design. All three groups of participants were concerned about professionalism and discipline using mobile resources, especially social media. Educators all expect students to have a certain level of digital skills. However, some students are discouraged by mobile resources. Students were likely to use a mobile learning resource if it was recommended by an educator or peer. There were concerns from all participants about fostering a reliance on navigation at the expense of knowledge and how this might impact on the standard of clinical acumen. This reflects similar concerns of dependence reported in the literature (Maudsley et al., 2018). Only one participant, a senior educator, suggested forming a focus group with students to discuss mobile resources. No student suggested something similar. Mobile collaboration experience amongst participants was limited.

In the second round of interviews, post-pandemic students reported increased motivation to find resources for themselves. Educators believed an increased use of mobile resources in education reflected an increase in clinical practice at that time. It was also felt that online teaching needed a foundation of physical learning to build on. It was still felt that students required guidance on identifying resources of good quality. There was a perception that a feature of the pandemic was a lot of misinformation online. Both educators and senior educators admitted to a lot of improvisation at the start of the pandemic with student safety a priority. Concerns regarding student pastoral support and value for money were voiced. Senior educators had switched to virtual student assessment which had paired back some of the domains being assessed. Some of the changes were not viewed entirely negatively with a major positive being the ability for students to learn independent of the location at a time to suit them.

References

Amara, S., Macedo, J., Bendella, F., & Santos, A. (2016). Group formation in mobile computer

supported collaborative learning contexts: a systematic literature review. Journal of Educational

Technology & Society, 19, 258–273.

Anderson P (2007) What is Web 2.0? Ideas, technologies and implications for Education. JISC Report. (http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/techwatch/tsw0701b.pdf;

accessed 15 May 2018)

Arnbjörnsson, Einar. (2014). The Use of Social Media in Medical Education: A Literature Review. Creative Education. 5. 2057-2061. 10.4236/ce.2014.524229.

Berge, Z., & Muilenburg, L. (2013). Handbook of mobile learning. London: Routledge

Bevan, M. (2014). A Method of Phenomenologica Interviewing. Qualitative Health Research, 24(1), pp.136-144.

Bhardwa, S. (2017). Complete University Guide reveals its top UK universities 2018. [online] Times Higher Education (THE). Available at: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/news/complete-university-guide-reveals-its-top-uk-universities-2018 [Accessed 20 Jan. 2019].

Boudry, C. (2015). Web 2.0 Applications in Medicine: Trends and Topics in the Literature. Medicine 2.0, 4(1), p.e2.

Bryman, A., 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chase, T., Julius, A., Chandan, J., Powell, E., Hall, C., Phillips, B., Burnett, R., Gill, D. and Fernando, B. (2018). Mobile learning in medicine: an evaluation of attitudes and behaviours of medical students. BMC Medical Education, 18(1).

Cheston, C., Flickinger, T. and Chisolm, M. (2013). Social Media Use in Medical Education: a systematic review. Academic Medicine, 88(6), pp.893-901.

Choi, B., Jegatheeswaran, L., Minocha, A. et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: a national survey. BMC Med Educ 20, 206 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02117-1

Christensen, Larry & Johnson, R. & Turner, Lisa. (2010). Research methods, design, and analysis

Clancy, M. (2013). Is reflexivity the key to minimising problems of interpretation in phenomenological research?. Nurse Researcher, 20(6), pp.12-16.

Cole, D., Rengasamy, E., Batchelor, S., Pope, C., Riley, S. and Cunningham, A. (2017). Using social media to support small group learning. BMC Medical Education, 17(1).

Conole G (2017) ’Research through the generations: Reflecting on the past, present and future’, Irish Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning 2(1): 1–21

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications, Inc.

Creswell, John. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Method Approaches.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five

approaches. Sage.

Davies, B., Rafique, J., Vincent, T., Fairclough, J., Packer, M., Vincent, R. and Haq, I. (2012). Mobile Medical Education (MoMEd) - how mobile information resources contribute to learning for undergraduate clinical students - a mixed methods study. BMC Medical Education, 12(1).

Davies, S., Mullan, J. and Feldman, P. (2017). Rebooting learning for the digital age. Oxford: Oxuniprint.

Demb, A., Erickson, D., & Hawkins-Wilding, S. (2004). The laptop alternative: Student reactions and strategic implications. Computers & Education, 43(4), 383-401. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2003.08.008

Dimond, R., Bullock, A., Lovatt, J. and Stacey, M. (2016). Mobile learning devices in the workplace: ‘as much a part of the junior doctors’ kit as a stethoscope’?. BMC Medical Education, 16(1).

Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al-Nusair L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 2020 Nov 5;10(11):e042378. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378. PMID: 33154063; PMCID: PMC7646323.

Duval, E., Sharples, M. and Sutherland, R. (2017). Technology Enhanced Learning. Springer International Publishing, pp.1-10.

Emanuel EJ. The inevitable reimagining of medical education. JAMA 2020; 323: 1127-28.

Ferrell, G., Smith, R. and Knight, S., 2018. Designing learning and assessment in a digital age. [online] Jisc. Available at: <https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/designing-learning-and-assessment-in-a-digital-age> [Accessed 4 March 2018].

Flannigan, C. and McAloon, J. (2011). Students prescribing emergency drug infusions utilising smartphones outperform consultants using BNFCs. Resuscitation, 82(11), pp.1424-1427.

Flickinger, T., O'Hagan, T. and Chisolm, M. (2015). Developing a Curriculum to Promote Professionalism for Medical Students Using Social Media: Pilot of a Workshop and Blog-Based Intervention. JMIR Medical Education, 1(2), p.e17.

Fu, Q.K. & Hwang, G.J. (2018). Trends in mobile technology-supported collaborative learning: A systematic review of journal publications from 2007 to 2016. Computers & Education, 119(1), 129-143. Elsevier Ltd

Gishen F, Bennett S, Gill D. Covid-19—the impact on our medical students will be far-reaching. 2020. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/04/03/covid-19-the-impact-on-our-medical-students-will-be-far-reaching/ (accessed 25 May 2020) Google Scholar

Glasziou, PP., Sawicki, PT., Prasad, K. and Montori, VM. (2011). Not a medical course, but a life course. International Society for Evidence-Based Health Care. Acad Med; 86:e4

General Medical Council. Information for medical students. 2020. https://www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/coronavirus-information-and-advice/information-for-medical-students (accessed 25 May 2020) Google Scholar

Golenhofen, N., Heindl, F., Grab‐Kroll, C., Messerer, D., Böckers, T. and Böckers, A. (2019). The Use of a Mobile Learning Tool by Medical Students in Undergraduate Anatomy and its Effects on Assessment Outcomes. Anatomical Sciences Education.

Gomes, A., Butera, G., Chretien, K. and Kind, T. (2017). The Development and Impact of a Social Media and Professionalism Course for Medical Students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 29(3), pp.296-303.

Gordon M, Patricio M, Horne L, Muston A, Alston SR, Pammi M et al. Developments in medical education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid BEME systematic review: BEME

Guide No. 63. Med Teach 2020; 42: 1202-15.

Green BL, Kennedy I, Hassanzadeh H, Sharma S, Frith G, Darling JC. A semi-quantitative and thematic analysis of medical student attitudes towards M-Learning. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015 Oct;21(5):925-30. doi: 10.1111/jep.12400. Epub 2015 Jul 7. PMID: 26153482.

Greene, J., Copeland, D., Deekens, V. and Yu, S. (2018). Beyond knowledge: Examining digital literacy's role in the acquisition of understanding in science. Computers & Education, 117, pp.141-159.

Hagler A. The Pros and Cons of Teaching with Zoom. 2019. http://www.teachingushistory.co/2019/09/the-pros-and-cons-of-teaching-with-zoom.html (accessed 6 July 2020) Google Scholar

Heacademy.ac.uk. (2017). Flipped learning | Higher Education Academy. [online] Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/flipped-learning-0 [Accessed 10 Jun. 2019].

Heacademy.ac.uk. (2018). mLearning | Higher Education Academy. [online] Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/mlearning [Accessed 25 Aug. 2018].

Health Education England. (2018). Digital literacy. [online] Available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/digital-literacy [Accessed 3 May 2019].

He J, Lo D C-T, Xie Y and Lartigue J (2016) ‘Integrating Internet of Things (IoT) into STEM undergraduate education: Case study of a modern technology infused courseware for embedded system course’, paper presented at the Frontiers in Education (FIE) conference, Erie, PA

Hempel, G., Neef, M., Rotzoll, D., & Heinke, W. (2013). Study of medicine 2.0 due to Web 2.0?! -- risks and opportunities for the curriculum in Leipzig. GMS Zeitschrift fur medizinische Ausbildung, 30(1), Doc11.

Hollander, R., 2017. Two-thirds of the world's population are now connected by mobile devices. [online] Business Insider. Available at: <https://www.businessinsider.com/world-population-mobile-devices-2017-9?r=US&IR=T> [Accessed 2 February 2018].

Hollinderbäumer, A., Hartz, T., & Uckert, F. (2013). Education 2.0 -- how has social media and Web 2.0 been integrated into medical education? A systematical literature review. GMS Zeitschrift fur medizinische Ausbildung, 30(1), Doc14.

Hwang, G. J., & Tsai, C. C. (2011). Research Trends in Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning: A Review of Publications in Selected Journals from 2001 to 2010. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42, E65-E70.

Jaffar, A. (2013). Exploring the use of a facebook page in anatomy education. Anatomical Sciences Education, 7(3), pp.199-208.

Jaldemark, J., Hratinski, S., Olofsson, A. and Öberg, L. (2017). Collaborative learning enhanced by mobile technologies: New perspectives and opportunities | BERA. [online] Bera.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/collaborative-learning-enhanced-by-mobile-technologies [Accessed 30 Feb. 20

Kay D, Pasarica M. Using technology to increase student (and faculty satisfaction with) engagement in medical education. Adv Physiol Educ. 2019; 43(3):408–413. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00033.2019 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kirschner, Paul & De Bruyckere, Pedro. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education. 67. 135-142. 10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.001.

Klímová, B. (2018). Mobile Learning in Medical Education. Journal of Medical Systems, 42(10).

Koohestani, H. R., Soltani Arabshahi, S. K., Fata, L., & Ahmadi, F. (2018). The educational effects of mobile learning on students of medical sciences: A systematic review in experimental studies. Journal of advances in medical education & professionalism, 6(2), 58–69.

Kukulska-Hulme, A., Sharples, M., Milrad, M., Arnedillo-Sánchez, I., & Vavoula, G.

(2011). The genesis and development of mobile learning in Europe. In D. Parsons (Ed.), Combining E-larning and m-learning: New applications of blended resources (pp. 151-177). IGI Global. doi: 10.4018/978-1-60960-481-3.ch010

Kuo, C.-L. (2005). Wireless technology in higher education: The perceptions of faculty and students concerning the use of wireless laptops. (Doctoral Disseration), Ohio University, Ohio, OH. Retrieved

from http://etd.ohiolink.edu/etd/ (1125521504) OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center database

Laurillard, D. (2007). Pedagogical forms for mobile learning. In N. Pachler (Ed.), Mobile learning: Towards a research agenda (pp. 153-175). London, UK: WLE Centre.

Lie, D., Trial, J., Schaff, P., Wallace, R. and Elliott, D. (2013). “Being the Best We Can Be”. Academic Medicine, 88(2), pp.240-245.

Liyanagunawardena, T. and Williams, S. (2014). Massive Open Online Courses on Health and Medicine: Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(8), p.e191.

Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The Transformational Effects of COVID-19 on Medical Education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033–1034. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14136

MacCallum, K., & Jeffrey, L. (2009). Identifying discriminating variables that determine mobile learning adoption by educators: An initial study. In R. J. Atkinson & C. McBeath (Eds.), Same places, different spaces. Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE 2009) (pp. 602-608). Auckland, New Zealand: ASCILITE.

Mason, J. (2002) Qualitative Researching. 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, London.

Maudsley, G., Taylor, D., Allam, O., Garner, J., Calinici, T. and Linkman, K. (2018). A Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review of: What works best for health professions students using mobile (hand-held) devices for educational support on clinical placements? BEME Guide No. 52. Medical Teacher, 41(2), pp.125-140.

McDonald, N., 2018. Digital in 2018: World’s internet users pass the 4 billion mark - We Are Social USA. [online] We Are Social USA. Available at: <https://wearesocial.com/us/blog/2018/01/global-digital-report-2018> [Accessed 30 January 2018].

McInnerney, T. (2018). Online Learning: Social Interaction and the Creation of a Sense of Community.. [online] Eric.ed.gov. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ853737 [Accessed 26 Aug. 2018].

Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mesko, B., Győrffy, Z. and Kollár, J. (2015). Digital Literacy in the Medical Curriculum: A Course With Social Media Tools and Gamification. JMIR Medical Education, 1(2), p.e6.

Neves, J. and Hillman, N. (2018). Student Academic Experience Survey 2018. [online] Hepi.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/STRICTLY-EMBARGOED-UNTIL-THURSDAY-7-JUNE-2018-Student-Academic-Experience-Survey-report-2018.pdf [Accessed 1 Feb. 2019].

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage Publications, Inc.

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy?. Computers & Education, 59(3), pp.1065-1078.

Ntloedibe‐Kuswani, GS. (2014). Disruptive e-Mobile Learning Model. TRANSACTION ON ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONIC CIRCUITS AND SYSTEMS. VOL. 4. PP. 7-14.

Officeforstudents.org.uk. (2019). What is the TEF? - Office for Students. [online] Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/teaching/what-is-the-tef/ [Accessed 1 Jun. 2019].

Rainbow S, Dorji T. Impact of COVID-19 on medical students in the United Kingdom. Germs. 2020;10(3):240-243. Published 2020 Sep 1. doi:10.18683/germs.2020.1210

Parsons D (2014) ‘A mobile learning overview by timeline and mind map’, International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning 6(4): 1–21

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pedro, L., Barbosa, C. and Santos, C. (2018). A critical review of mobile learning integration in formal educational contexts. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1).

Pickering, J. and Bickerdike, S. (2016). Medical student use of Facebook to support preparation for anatomy assessments. Anatomical Sciences Education, 10(3), pp.205-214.

Potter, L. (2018). About | Geeky Medics. [online] Geeky Medics. Available at: https://geekymedics.com/about/ [Accessed 9 Jun. 2019].

Ravindran, R., Kashyap, M., Lilis, L., Vivekanantham, S. and Phoenix, G. (2014). Evaluation of an online medical teaching forum. The Clinical Teacher, 11(4), pp.274-278.

Roblyer, M. D., & Doering, A. H. (2010). Integrating educational technology into teaching (5th ed.). New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon.

Scheibe M, Reichelt J, Bellmann M, Kirch W. Acceptance factors of mobile apps for diabetes by patients aged 50 or older: a qualitative study. Med 2 0. 2015 Mar 2;4(1):e1. doi: 10.2196/med20.3912. PMID: 25733033; PMCID: PMC4376102.

Sha, L., Looi, C. K., Chen, W., & Zhang, B. H. (2012). Understanding mobile learning from the perspective of self-regulated learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(4), 366-378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00461.x

Shenson, J., Adams, R., Ahmed, S. and Spickard, A. (2015). Formation of a New Entity to Support Effective Use of Technology in Medical Education: The Student Technology Committee. JMIR Medical Education, 1(2), p.e9.

Smith A, Bullock S. COVID-19: initial guidance for higher education providers on standards and quality. 2020. https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/guidance/covid-19-initial-guidance-for-providers.pdf (accessed 25 May 2020) Google Scholar

Sung, Y., Yang, J. and Lee, H. (2017). The Effects of Mobile-Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: Meta Analysis and Critical Synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 87(4), pp.768-805.

Swinnerton, B., Morris, N., Hotchkiss, S. and Pickering, J. (2016). The integration of an anatomy massive open online course (MOOC) into a medical anatomy curriculum. Anatomical Sciences Education, 10(1), pp.53-67.

Traxler, J., & Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2016). Mobile learning: the next generation. London: Routledge

Vogelsang, M., Rockenbauch, K., Wrigge, H., Heinke, W., & Hempel, G. (2018). Medical Education for "Generation Z": Everything online?! - An analysis of Internet-based media use by teachers in medicine. GMS journal for medical education, 35(2), Doc21. doi:10.3205/zma001168

Wolanskyj-Spinner AP. COVID-19: the global disrupter of medical education. https://www.ashclinicalnews.org/viewpoints/editors-corner/covid-19-global-disrupter-medical-education/ (accessed 25 May 2020) Google Scholar

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.