I was lucky to present at the rearranged AOME Spring Conference on 16th September 2021.

This blog post is about the project I presented.

Below you can find a recording of my presentation, my slide set (complete with navigation) and full details of the project’s background, methodology and findings.

Abstract

As technology has developed so the focus of mobile learning has moved toward collaborative practice. It has been shown that educator attitude and student engagement in the process of developing mobile resources are key to the success of mobile collaboration. Best practice will therefore require an understanding of student and educator perceptions toward mobile learning. Yet research into the perceptions of medical students in the UK towards mobile learning is limited to the evaluation of a specific resource. There has been no study performed in the UK exploring the perceptions of medical educators.

The COVID-19 pandemic was obviously disruptive to medical education yet has been described as a catalyst for transformation which had been “brewing” for a decade1. There was early recognition that moving to virtual education represented an “alternative way of learning”2. The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of UK medical educators and students towards mobile learning using the University of Nottingham as a case study. Perceptions post-pandemic were compared to those beforehand.

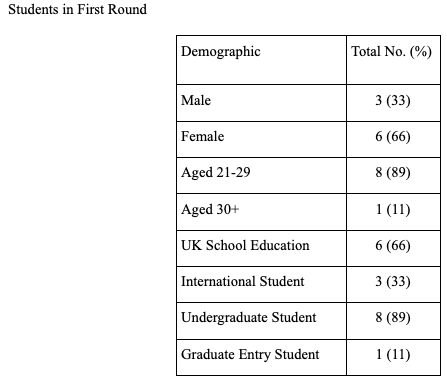

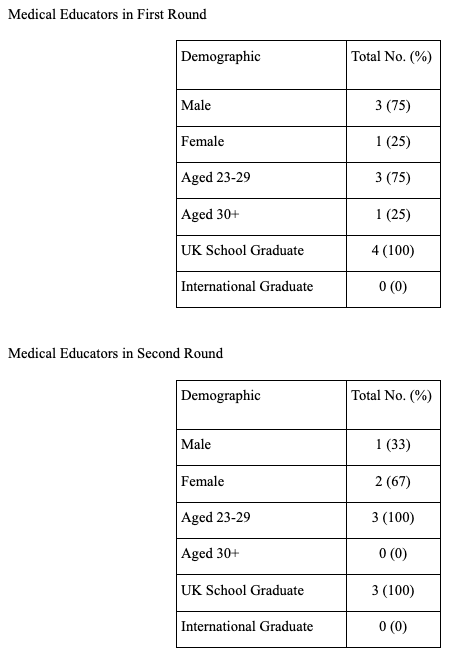

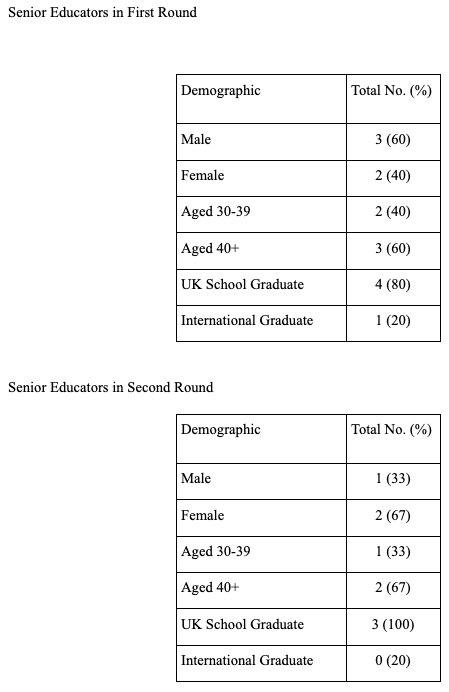

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in 2019 with 9 third-year medical students, 4 clinical teaching fellows with day-to-day teaching duties, and 5 senior medical educators with university roles in curriculum design, e-Learning, and assessment. A further round of semi-structured interviews was conducted in 2020 with 7 third-year medical students, 3 fellows, and 3 senior medical educators. Three of the educators were in both rounds. Following transcription hermeneutic phenomenological analysis was performed for each participant and then each cohort.

Participants in both rounds viewed mobile resources only as an adjunct to traditional teaching. It was suggested as being best used for senior students or in postgraduate education. Educators do not perceive all mobile resources to be of equal value and are particularly mixed regarding social media. Students in the first round were only likely to use resources if recommended by an educator or peer. Students in the second round self-reported an increased motivation to seek out resources for themselves. Educators were only likely to recommend resources they used themselves. It was felt in both rounds that students require guidance on evaluating resources. This need was felt to have increased since the pandemic. Participants were concerned about fostering a reliance on mobile resources but this was felt to be unavoidable in the second round.

References:

1 Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The Transformational Effects of COVID-19 on Medical Education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033–1034. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14136

2 Ahmad Al Samaraee. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education. 2020. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 1-4. 81. 7. 10.12968/hmed.2020.0191.32730144

Background

The Higher Learning Academy (HLA) defines mobile learning as: “the use of mobile devices to enhance personal learning across multiple contexts” (Heacademy.ac.uk, 2018). Technology-enhanced learning (TEL) is an evolving field building from developments within both learning and technology over decades (Conole, 2017; Parson, 2014). Mobile learning has become a key component of this with a number of social and technological phenomena behind its rise (Heacademy.ac.uk, 2018).

One is the increasing access to mobile technology amongst students. Indeed, since 2000 there has been a significant shift in the literature towards appreciating that no understanding of mobile learning would be possible without viewing it through the prism of social and cultural trends (Kukulska-Hulme, Sharples, Milrad, Arnedillo-Sánchez, & Vavoula, 2011). More than 4 billion people, over half the world’s population, now have access to the internet, with two-thirds using a mobile phone; more than half of which are smartphones (McDonald, 2018). By 2020, 66% of new global connections between people will occur via a smartphone (Hollander, 2017).

Another development is what can actually be achieved with that access. We are now in the era of the internet of things (He et al, 2016) such as touchscreen phones and tablets as well as smart wearables such as glasses or watches. Jaldermark et al (2017) therefore described humans as “technology equipped mobile creatures that are using applications, devices, and networks as a platform for enhancing their learning in both formal and informal settings.” They argued further that as society is now heavily characterised by the widespread use of mobile devices and the connectivity they afford there is a need to re-conceptualise the idea of learning in the digital age.

The original version of the Internet (so-called Web 1.0) saw a limited number of resources with most users accessing the Internet to browse (Anderson, 2007). Most text was hypertext (electronically linked non-linear text) with a similar approach to learning as a student would use with a book (Kintsch, 1997). Therefore, the early Internet and its use fitted into previous pedagogy. Subsequent developments have focused on collaboration and the ability to create and edit resources. This is Web 2.0 technology or the ‘participatory web’. Students can now produce resources themselves and share via social media rather than through traditional forms of publication. A prominent example of this is the website ‘Geeky Medics’ created in 2010 by a then medical student as a forum to share notes and learning. By 2018 geekymedics.com had grown with over 50 million visits from more than 150 countries accessing material varying from blogs to videos and a smartphone application (Potter, 2018).

Web 2.0 has been described as “disruptive” (Ntloedibe-Kuswan, 2014) to traditional education. With unprecedented access and resources, mobile learning has been described as ubiquitous learning (Hwang and Tsai, 2011). The opportunities of Web 2.0 resulted in academic interest; the average annual growth rate of biomedical publications related to Web 2.0 since 2002 was 106.3% and by 2015 Web 2.0 was well integrated into the academic field (Boudry, 2015).

The era of smart devices includes the emergence of different touchscreen devices with opportunities for instant social and technological networking independent of time and place. Devices such as small portable laptops, smartphones, tablets, and, more recently, various wearable devices have made up a mobile technological platform enabling an online community for students (Moubarak et al, 2010) The emergence of mobility as an essential aspect of everyday life underlines a need to update the conceptualisations of how we learn (Traxler & Kukulska-Hulme, 2016).

Besides awareness of the rapid technological development, it is also important to understand its impact on the learners' context and how learners communicate with each other (Amara, Macedo, Bendella, & Santos, 2016). As a result, a field of mobile learning has emerged, which focuses on how collaborative learning could be enhanced by applying various mobile technologies (Berge & Muilenburg, 2013; Traxler & Kukulska-Hulme, 2016). As mobile technology has developed toward increasing connectivity so understanding of mobile learning has trended toward a focus on collaboration.

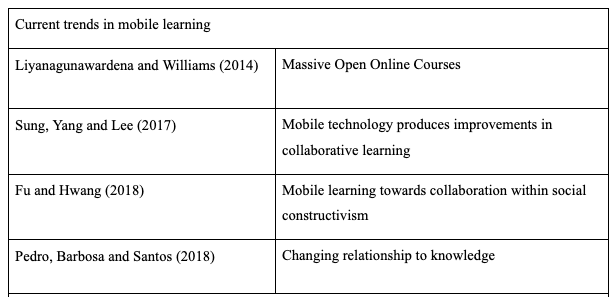

Mobile-computer-supported collaborative learning (mCSCL) describes the deliberate use of mobile resources and technology to collaborate with learning (Sung, Yang, and Lee, 2017). This novel field represents the general trend of mobile learning (Fu and Hwang, 2018). This trend embraces an understanding of how to enhance mobile technologies through collaboration as well as observing and evaluating collaborative learning activities in everyday informal and formal educational settings. (Jaldemark et al., 2017). It also informs understanding of how learning is provided in a society characterised by an emerging digitalisation (Duval, Sharples, & Sutherland, 2017; Traxler & Kukulska-Hulme, 2016).

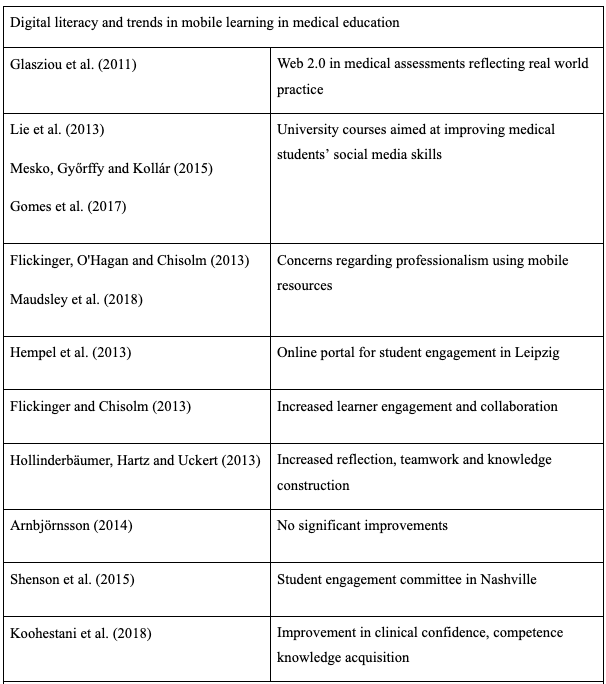

In Hungary optional (Mesko, Győrffy and Kollár, 2015) and in the USA compulsory (Gomes et al., 2017) courses for medical students on digital literacy and utilising Web 2.0 resources have been developed. The use of mobile resources has been shown in the UK to help with a student’s transition to clinical practice (Dimond et al., 2016) as it reflects current practice.

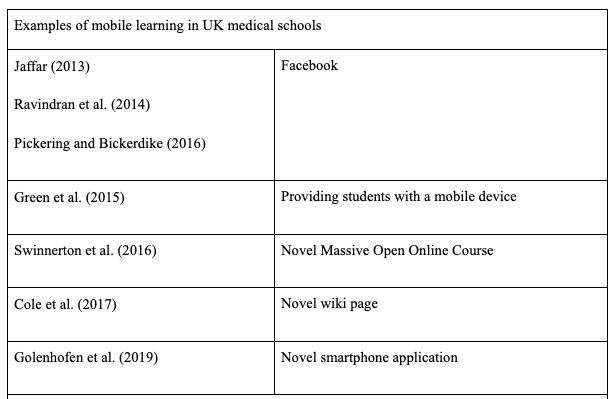

Despite the benefits and challenges of mobile learning within medical education in the United Kingdom, there are no national guidelines for its implementation or strategic use. Research in the UK focuses on initiating a particular intervention and surveying student opinion (Cole et al., 2017; Pickering and Bickerdike, 2016; Ravindran et al., 2014). Results have been mixed. It has been shown that medical students prefer learning with mobile technology (Davies et al., 2017) and they react positively to mobile learning (Chase et al., 2018). However, in another study when presented with an online course medical students reported a preference for traditional learning (Swinnerton et al., 2016). This reflects the most recent findings of a student survey published by the Higher Education Policy Institute (Neves and Hillman, 2018) suggesting that students prefer traditional contact time over all other learning events. Students nationally report dissatisfaction with current levels of contact time with their educators (Neves and Hillman, 2018).

Students in the UK are conservative in their preferences of learning methods and engagement with them prior to introducing mobile resources is a key step in their success (Davies, Mullan and Feldman, 2018). There is a growing list of case studies of UK universities utilising some form of the student body to consult their opinions prior to introducing mobile learning in the curriculum (Davies, Mullan and Feldman, 2018; Ferrell, Smith and Knight, 2018). Examples of similar student engagement bodies within medical education have been established in the US (Shenson et al., 2015) and Germany (Hempel et al., 2013) but within the UK there is a dearth of work into this area in medical education.

Systematic reviews into Web 2.0 resource use in medical education have shown that educator attitude is also an important step with opportunities to change educator practice (Cheston, Flickinger and Chisolm, 2013; Hollinderbäumer, Hartz & Uckert, 2013). However, whilst there is evidence from Germany of medical educator negativity toward using certain Web 2.0 resources (Volgelsang et al., 2018) there is limited evidence as to the attitude of medical educators in the UK toward Web 2.0 or mobile learning in general. However, it has been suggested they are less likely to engage with mobile resources than their students (Cole et al., 2017).

Literature Review

Towards mobile collaborative learning

Since the year 2000 literature exploring mobile learning has increasingly focused on the learning process, the preferences of the learner, and collaboration. Kreijns, Kirschner, and Jochems (2002) proposed that there were five stages to learning through mobile collaboration: copresence, awareness, communication, collaboration, and coordination. They also identified that attempting online collaboration placed pressure on educators to ensure it took place amongst their learners. This observation has continued in the literature and it is well recognised that online collaboration is a phenomenon that does not spontaneously occur amongst learners (Zhao, Sullivan, & Mellenius, 2014). Collaboration is important for building knowledge (Mylläri, Åhlberg, & Dillon, 2010) and finding meaning (Yang, Yeh, & Wong, 2010).

However, the unique features of mobile devices, in particular their portability, social connectivity, and a sense of individuality mean they make online collaboration more likely as opposed to desktop computers that don’t have those features (Chinnery, 2006; Gao, Liu, & Paas, 2016; Lan & Lin, 2016; Song, 2014; Zheng & Yu, 2016). Mobile devices have been credited with making learning movable, real-time, seamless, and collaborative (Kukulska-Hulme, 2009; Wong and Looi, 2011). A meta-analysis of 48 peer-reviewed journal articles and doctoral dissertations from 2000 to 2015 revealed that mobile technology has produced meaningful improvements to collaborative learning (Sung, Yang, and Lee, 2017).

As discussed before the role of mobile learning to foster collaboration between learners has been described as mobile-computer-supported collaborative learning (mCSCL). This distinction arose from developments of mobile technology and how it can be integrated into teaching activities based upon learner cooperation (Zurita & Nussbaum, 2007). This distinction within pedagogy would not have been possible without the empowering nature of mobile devices and resources (Song, 2014).

The majority of literature looking at TEL and mobile learning within medical education focuses on more traditional courses. Analysis of literature pertaining to TEL use within only problem-based learning (PBL) reveals similar strengths to traditional courses; accessing information, collaboration and reflection, and weaknesses; infrastructure demand and the need for teacher and staff engagement (Cheston, Flickinger and Chisolm, 2013) (Jin and Bridges, 2014). Meta-analysis of the literature on mobile learning in PBL found that problem-solving is one of the major cognitive skills emphasised and that device and implementation aspects are the main limitations to mobile learning use in PBL (Ismail et al., 2016).

Digital literacy and Medicine

Health Education England (HEE) defines digital literacy as, “those capabilities that fit someone for living, learning, working, participating and thriving in a digital society" (Health Education England, 2018). In announcing their Building a Digital Ready Workforce programme HEE argued that, “every single organisation in health and social care has a duty for the learning and development of its own staff and we believe that digital skills and knowledge should be a core component of this.” It’s been argued that social media helps to provide patient education and so introducing students to social media helps to prepare them for “the world of empowered patients” (Mesko, Győrffy, and Kollár, 2015) as well as reflecting an adaptable curriculum (Gomes et al., 2017). Professional courses focussing on medical students’ use of social media have been shown to foster continued self-monitoring (Lie et al., 2013). One example from Hungary was an elective course for students designed to support online behaviour and information management with a special emphasis on social media (Mesko, Győrffy, and Kollár, 2015). A similar compulsory course has been designed in the United States for first-year medical students based on student usage of social media with discussion with peers and educators (Gomes et al., 2017). Whilst the course in Hungary focussed on efficient use of mobile resources the US course prioritised students’ professionalism and use of social media to aid their careers. Both reported positive outcomes. In the UK a Digital Literacies course was introduced into the medical curriculum at Imperial College London starting in the first year and extending longitudinally throughout the course. It is claimed that this course, “looks to the future impacts of digital technologies on the medical profession” (Digitalstudent.jiscinvolve.org, 2014). However, unlike the US and Hungary courses, no publication has resulted from the UK course.

Another aspect interlinked with these social and technological changes has been the shortening of the half-life of knowledge. In 2008 half of all knowledge learned on a university degree was obsolete within 2 years (Tucker, 2008). By 2017 the half-life of medical knowledge was estimated at 18-24 months. It is estimated that by 2021 it will be only 73 days (Colacino, 2017). It’s been argued that with increasing in situ mobile access learners increasingly perceive knowledge as disposable and ephemeral (Pedro, Barbosa, and Santos, 2018). The use of Web 2.0 as part of open-book assessments has been suggested as a potential development in medical education in order to reflect real-world practices and to develop digital literacy (Glasziou et al., 2011).

A Best Evidence Medical Education review of 49 abstracts on mobile learning for health profession students on clinical placement showed powerful education support, especially with transitions from student to professional reflecting the demand for digital literacy within Medicine. However, there were concerns especially with professionalism, confidentiality, mixed messages, and distractions when using mobile resources (Maudsley et al., 2018). This theme regarding professionalism was reflected in other studies (Flickinger, O'Hagan, and Chisolm, 2015)

Student perceptions of mobile resources

The term ‘digital natives’ coined by Prensky (2001) describes students for whom technology has been an indelible part of their development and education. This led to debate regarding how digital nativism might shape education and the potential differences between those who have been born into technology and those who have adapted to it; termed digital immigrants. However, the latest evidence suggests that this distinction is not as clear as at first believed and this presumption of digital literacy based on youth might hamper education (Kirschner and De Bruyckere, 2017). An Introduction to e-Learning course delivered to undergraduate students in Australia suggested that ‘digital natives’ are not familiar with education technologies and need to be made aware of and explicitly taught about them (Ng, 2012) whilst subjects aged over 50 can adapt to an unfamiliar mobile resource (Scheibe et al., 2015). It has been recently shown that students can be taught through learning tasks to improve how they process digital learning resources (Greene et al., 2018). Through teaching sessions, the digital literacy of digital natives can be improved (Ng, 2012). Mobile learning can positively affect students’ learning in all three domains of Bloom’s taxonomy (Koohestani et al., 2018).

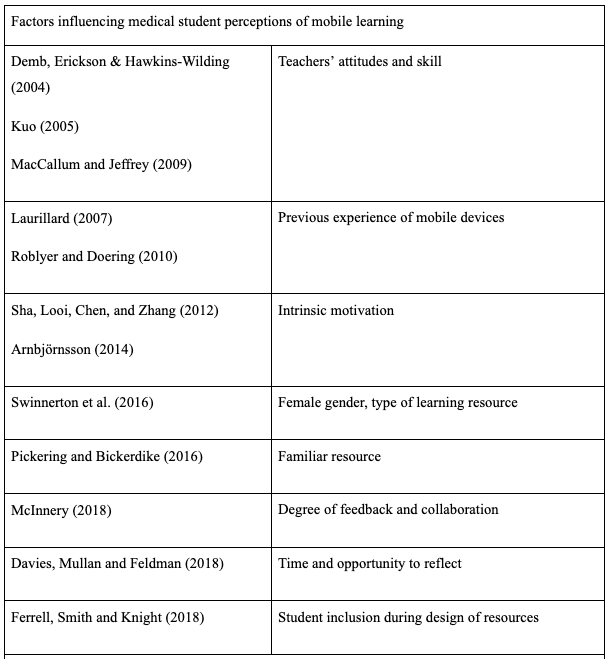

A common theme across the literature regarding student perceptions towards mobile learning is the research design of implementing a mobile resource and then evaluating perceptions. For example, in one particular study exploring UK students’ attitudes towards mobile learning (Green et al., 2015) it was suggested that mobile learning enhanced education. However, this study, whilst focusing on student preferences and barriers to usage, also surveyed students following implementing a specific intervention, in this case providing students with a mobile device with tailored resources. For the purposes of this study, this made it hard to specifically find literature exploring student attitudes towards mobile learning recorded in isolation. Therefore, the conclusions of the literature were reviewed but I was mindful these were conclusions following a specific intervention.

Various interventions are being used in the literature. Facebook in particular is being increasingly used in medical education as it offers forum and messaging services (Pickering and Bickerdike, 2016, Jaffar, 2013, Ravindran et al., 2014). Another option is the creation of novel mobile learning resources such as a Wiki platform created for first-year medical student case-based discussion at Cardiff Medical School (Cole et al., 2017). A MOOC has been used at Leeds Medical School to support first-year medical students with their anatomy teaching (Swinnerton et al., 2016). Novel applications have been designed and used to supplement traditional teaching (Golenhofen et al., 2019).

In a systematic review of published literature on social media use in medical education Cheston, Flickinger, and Chisolm (2013) found an association with improving knowledge, attitudes, and skills. The most often reported benefits were in learner engagement, feedback, collaboration, and professional development. The most commonly cited challenges were technical difficulties, unpredictable learner participation, and privacy/security concerns. A systematic review from the same year reported a dominance of literature from the US and Great Britain. (Hollinderbäumer, Hartz and Uckert 2013). It suggested that learning through Web 2.0 was a form of self-deterministic learning and increases reflection, knowledge construction, and teamwork. A year later however Arnbjörnsson (2014) reviewed only publications that included randomisation, reviews, and meta-analyses and concluded that despite the wide use of social media no studies reported significant improvements in the learning process and that some novel mobile learning resources don’t result in better student outcomes.

All of these systematic reviews were limited in the available literature with only 14 studies (Cheston, Flickinger and Chisolm, 2013), 20 studies (Hollinderbäumer, Hartz and Uckert 2013) and 25 studies (Arnbjörnsson, 2014) reviewed. A later systematic review of 21 studies from 2007 to 2017 (Koohestani et al., 2018) showed three themes: improvement in student clinical confidence and competence, improvements in the acquisition and enhancing theoretical knowledge, and positive attitudes of students toward mobile learning. However, only one of those studies was conducted in the United Kingdom. This was a study comparing student use of a mobile drug calculator to using the British National Formulary for Children (BNFC). Utilising the smartphone was significantly more accurate and faster and increased prescriber confidence. Medical students using the smartphone outperformed consultant paediatricians using the BNFC (Flannigan and McAloon, 2011).

Students quickly adapt their usage of Web 2.0 resources to fit a preferred way of working (Cole et al., 2017, Ng, 2012). Female students seem more likely to approach online learning in a more personalised manner (Swinnerton et al., 2016). Using a familiar social media platform helps increase confidence and decrease anxiety (Pickering and Bickerdike, 2016). Whilst it’s been suggested male students may be less likely to ask questions via a Web 2.0 resource (Pickering and Bickerdike, 2016) students overall seem to find these a safe environment and feel more comfortable asking questions than in a clinical area (Ravindran et al., 2014). There is evidence that certain learning resources are more readily engaged with than others with Swinnerton et al., 2016 reporting greater student appreciation toward videos and quizzes than discussion fora.

There has been some discussion that students are intrinsically motivated by mobile learning due to their experience of mobile devices (Laurillard, 2007 and Roblyer and Doering, 2010). Arnbjörnsson (2014) linked student usage of mobile resources to intrinsic motivation; the higher-achieving the student the more motivated they were and so the more likely they are to use a mobile resource.

A recent review of literature pertaining to mobile learning use in medical education suggests that it remains a supplement only. There still is not a consensus on the most efficient use of mobile learning resources in medical education but the ever-changing nature of resources means this is probably inevitable (Klímová, 2018).

It’s been suggested that while mobile learning offers incredible opportunities, it requires students to be motivated and able to self-regulate their learning (Sha, Looi, Chen, and Zhang, 2012). Terras & Ramsay, (2012) identified a number of psychological challenges for students using mobile learning including oversight of students and the management of information which often comes at disparate moments. Greene, Yu, and Copeland, (2014) suggested that effective digital literacy relies upon a student being able to effectively plan and monitor their own strategies as well as vetting material found. Medical students themselves report concerns regarding privacy and professional behaviour when using social media in education (Flickinger, O'Hagan, and Chisolm, 2015).

The most recent student survey by The Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) found that students prefer direct contact time with educators over other learning events. 44% of students rating their course as poor or very poor value for money included a lack of contact hours as part of their complaint. More students (19%) were dissatisfied with their contact time than neutral (17%) and had increased in the previous year. However, the survey did not explore mobile resources either as a contact time alternative or how students viewed their educators creating resources for them. (Neves and Hillman, 2018).

Teachers and Institutions

Whilst evidence points to mobile learning being enjoyable and increasing student engagement (Heath et al, 2018) it is shown that technology-based courses with a low sense of human feedback and collaboration will suffer the highest rates of student attrition (McInnery, 2018). Students in the UK are conservative in their preferences of learning methods and their university engaging with them prior to introducing mobile resources is a key step in the successful use of that resource. It, therefore, takes time for any novel teaching practice to become embedded with students needing to experience and reflect on their overall learning practice (Davies, Mullan, and Feldman, 2018).

Case studies in the UK show that the success of mobile learning in higher education has involved some degree of student inclusion alongside educators during design (Ferrell, Smith and Knight, 2018). No evidence of medical student inclusion during mobile resource design in the UK was found in the literature. One example was published from Vanderbilt University, Nashville; a committee formed of administrators, educators, and selectively recruited students. This committee serves four functions: to liaise between students and administration; advising the development of institutional educational technologies; developing, piloting, and assessing new student-led educational technologies; and promoting biomedical and educational informatics within the school community. The authors report benefits from rapid improvements to educational technologies that meet students’ needs and enhance learning opportunities as well as fostering a campus culture of awareness and innovation in informatics and medical education (Shenson et al., 2015).

An example from a European medical school was found in the Faculty of Medicine of Universität Leipzig, Germany. Rather than a physical committee their E-learning and New Media Working Group established an online portal for discussion with students over mobile resources as well as expanding the university’s presence across social media to help disseminate information (Hempel et al., 2013).

HEPI has recently made seven recommendations for successful provision of mobile learning at UK universities which include building technology into curriculum design and for a nationwide evidence and knowledge base to be developed on what works (Davies, Mullan and Feldman, 2018).

In 2017 the UK government established the Teaching Excellence Framework since renamed the Teaching Excellence and Student Outcome Framework (TEF), as a national exercise to assess the quality of higher education (Officeforstudents.org.uk, 2019). This assessment is based on student feedback, outcomes, and drop-out rates. The TEF results in an institute being awarded a gold, silver, or bronze award. HEPI argued that “Digital technology should be recognised as a key tool for higher education institutions responding to the TEF. Providers should be expected to include information on how they are improving teaching through the use of digital technology in their submissions to the TEF” (Davies, Mullan, and Feldman, 2018).

Both Cheston, Flickinger, and Chisolm, (2013) and Hollinderbäumer, Hartz and Uckert, (2013) suggested during their conclusions that Web 2.0 offered opportunities for educator innovation. However, it has been shown that teachers may be less engaged than their students in utilising Web 2.0 resources especially in accessing materials outside of the classroom (Cole et al., 2017).

Both students and teachers need to be trained prior to using Web 2.0 resources (Cole et al., 2017). Teachers’ attitudes toward and ability with mobile resources are a major influence on students (Kuo, 2005; Demb, Erickson & Hawkins-Wilding, 2004 and MacCallum and Jeffrey, 2009). Students’ fear of patient and teacher perception is reported as a barrier to using mobile resources but these fears may be due to hearsay rather than actually experience (Davies et al., 2012).

No literature exploring the perceptions of UK medical educators toward mobile learning was found. However, a recent online survey of 284 medical educators in Germany did show some interesting findings. Respondents valued interactive patient cases, podcasts, and subject-specific apps as the more constructive teaching tools while Facebook and Twitter were considered unsuitable as platforms for medical education. There was no relationship found between an educator’s demographics and their use of mobile learning resources (Volgelsang et al., 2018).

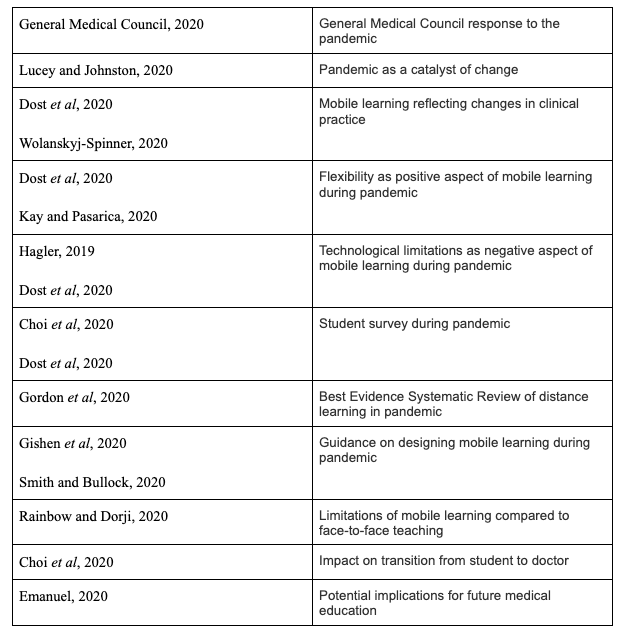

COVID-19 pandemic and mobile learning

Due to concerns regarding student safety, the COVID-19 pandemic saw a switch away from face-to-face teaching and clinical experience to mobile learning. This was obviously disruptive to medical education yet has been described as a catalyst for transformation which had been “brewing” for a decade (Lucey and Johnston, 2020).

In a cross-sectional, online national survey of medical students across 39 medical schools, respondents reported a 300% increase in the amount of time spent on online platforms following the pandemic. Flexibility was deemed to be the greatest perceived benefit whilst distractions from family and poor internet connection were the greatest downsides. Further incorporation of mobile learning with traditional methods of teaching was recommended, particularly focused on problem-based learning and teamwork. It was also felt that a move towards mobile learning would reflect the move towards remote clinical consultations as well (Dost et al, 2020). The positive aspect of flexibility, especially in students being able to learn in their own time, has been reported in other studies (Kay and Pasarica, 2020) as has the negative impact of technological limitations (Hagler, 2019). Concerns regarding the relevance of online medical education have stated that sessions simulating virtual consultations should be used (Wolanskyj-Spinner, 2020).

In the UK the General Medical Council (GMC) sped up the processing of final-year medical students’ applications for professional registration (General Medical Council, 2020). In another online survey of final-year medical students across 33 medical schools respondents felt that while changes to their curricula had been necessary, it had adversely affected their transition from student to doctor with regard to losing their clinical assistantships. Yet students still felt confident about going into their Foundation Year One (Choi et al, 2020). Concerns have been raised about how to meet students’ mental health needs remotely. (Rainbow and Dorji, 2020).

While it’s been argued that remote learning cannot replace face-to-face teaching in medical education it has proven to be a flexible and inexpensive way of delivering core content (Rainbow and Dorji, 2020). A Best Evidence in Medical Education systematic review found that adoption of remote learning had been rapid in many countries as a “new norm” at many levels but that evaluation had been “limited” (Gordon et al, 2020). Online sessions need to be planned in a similar way to face-to-face teaching (Smith and Bullock, 2020) and tailored to students’ levels of experience (Gishen et al, 2020). It’s also been argued that thanks to the pandemic, “tomorrow’s trainers” will have experienced the “reimagining” of medical education (Emanuel, 2020).

In summary, the trend of mobile learning is towards increasing collaboration. Digital literacy is a key skill within Medicine with some suggestions in the literature of an online community of practice being formed. Several medical schools are implementing modules to prepare their students for working in this new digital literate environment. Mobile learning has been suggested as working optimally in a flipped classroom blended learning approach. Evidence of students’ perceptions of mobile learning focuses on the evaluation of a specific resource or intervention rather than in isolation as a concept. However, there is growing evidence that student engagement early on in the design of a resource leads to better engagement with the resource once developed and released. Whilst there are examples of these groups in non-medical UK faculties as well as at medical schools in the US and Europe there is no evidence of an equivalent at a UK medical school. Educators are a major factor in students adopting a mobile resource. However, there is limited evidence of medical educator perceptions toward mobile learning and none from the UK.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been called a ‘catalyst’ for transformation and has seen students change their use of online resources. Concerns remain regarding the limitations of mobile learning which include technological and pastoral elements. Yet there is an argument that the changes reflect those seen in clinical practice and could affect the future of medical education.

The purpose of this phenomenological study was to explore how medical students and educators perceive mobile learning. Current literature is void of evidence regarding medical student perceptions toward mobile learning in isolation rather than related to a specific resource and its evaluation. Another void in the research concerns the perceptions of medical educators toward mobile learning. The voices of medical students and educators were at the core of this study as their lived experiences shed light on their perception of the phenomenon of mobile learning. A qualitative strategy was chosen to help navigate the investigatory process.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a key interpretivist and anti-positivist branch of social science research. Phenomenology has its roots in philosophy and is interested in the analysis and descriptive experience of phenomena by individuals in their everyday world; what is called their ‘lifeworld’ (Creswell, 2013). Therefore, the interest is in the real-world experience of an individual and not why it is that way. Any human experience is worth studying as phenomenologists perceive the human experience of the everyday world as a valid method of inquiry. This means that phenomenological research differs from other forms of qualitative research as it attempts to understand a particular phenomenon from the points of view of the participants who have experienced it (Christensen, Johnson, and Turner, 2010). The phenomenon in question for this study is mobile learning in medical education.

A phenomenological inquiry is “an attempt to deal with inner experiences unprobed in everyday life” (Merriam, 2002). Therefore a phenomenological method was chosen to help identify meaning behind the human experience as it related to a phenomenon or notable collective occurrence (Cresswell, 2009). The phenomenon of interest was how medical students and educators experience and perceive mobile learning in medical education.

Phenomenology is used extensively in research in the fields of sociology, psychology, health sciences, and education (Cresswell, 1998). This methodology was chosen to show “how complex meanings are built out of simple units of direct experience” (Merriam, 2002) and how “general or universal meanings are derived” from lived experience (Cresswell, 1998). After a phenomenological approach was deemed appropriate for this study its design was based on Moustakas (1994).

Moustakas described the steps in phenomenological analysis (Moustakas, 1994). First, he recommends giving each statement in the transcript equal weighting and value. This is part of the epoch process. Statements referring to the phenomenon in question are to be lifted out of the transcription and onto a separate sheet. These are the horizons of the transcription. This process is known as horizontalisation. Once the horizons for each participant are lifted the process of reduction and elimination can begin. Moustakas recommends two questions when analysing the horizons (Moustakas, 1994):

Does it contain a moment of the experience that is a necessary and sufficient constituent for understanding it?

Is it possible to abstract and label it?

Only if the answer to these questions is yes can the statement be labelled as an ‘invariant constituent’ of the experience and move on for further analysis by clustering and thematising the invariant constituents. These clustered themes allow textual descriptions to be constructed for each participant which then allows composite descriptions to be created for each category of participant.

The potential impact of the researcher on the participants’ responses as well as analysis is well established Creswell (2013). Reflexivity is an attitude of attending systematically to the context of knowledge construction, especially to the effect of the researcher, at every step of the research process so as to avoid bias and skewing analysis. It’s been recommended that during phenomenological study the researcher should employ regular breaks of time and place from the data as well as reflecting on their own emotions during analysis (Clancy, 2013). Breaks were taken before and after each stage of the phenomenological process so the researcher could encounter the data anew as much as possible.

As this study was not interested in generating theory the grounded theory approach was not considered appropriate. Grounded theory also requires multiple cycles which would not fit with this study’s time frame. This study was not attempting to create a consensus nor only consider the thoughts of experts and so the Delphi model was not selected. The mixed-methods approach was considered but early on it was felt any form of quantitative analysis would not offer any benefit compared to interviewing alone.

Phenomenological Case Study

Phenomenologists aim to examine the lived experiences of a particular group of people to best capture and describe their perceived realities within a certain context (Moustakas, 1994). Phenomenological research allows understanding of the essence of a human experience in order to gain a rich understanding of a particular experience from the perspective of the participant(s). These participants’ personal, firsthand knowledge provides descriptive data which provides the researcher a firmer understanding of the “lived experience” for a particular event (Patton, 2002). This phenomenological approach, used with the case study method, allows researchers to understand and/or make sense of intricate human experiences and “the essence and the underlying structure of a phenomenon” (Merriam, 2009).

Case studies are “anchored in real-life situations,” and they result in “…a rich and holistic account” of a particular phenomenon (Merriam, 2009). This design allows researchers to gain a more in-depth understanding of participants’ total experiences. Unlike quantitative analysis, where patterns in data are examined on a large scale, case studies allow researchers to observe and analyse data on a much smaller, intimate level. Utilising the case study design allows researchers to examine a given uniqueness in order to reveal a phenomenon that otherwise may not be accessible (Merriam, 2009). The researcher is able to come to understand the phenomenon through the participants’ descriptions of their lived experiences as well as search for the cruxes of those experiences (Moustakas, 1994). The results of case studies facilitate an understanding of real-life complexities that directly relate to readers’ routine, ordinary experiences.

Study Design

This was a qualitative study, which intended to explore the lived experiences of medical students and medical educators of mobile learning through phenomenological inquiry. Medical students and educators at the University of Nottingham were selected as a case study. Whilst case studies are often inextricably linked to a particular setting, sometimes the sample of data itself is the unit of interest with the location acting as a backcloth to the collection of data (Bryman, 2012). With a case study the case is an object of interest in its own right and the researcher aims to provide an in-depth examination of it.

This was felt to be a representative case. Representative cases are not extreme or unusual in any way but instead provide a suitable context for research questions to be answered (Bryman, 2012). They “capture the circumstances and conditions of an everyday or commonplace situation” (Yin, 2009). To this end, medical students and educators at the University of Nottingham were felt to be a representative case to explore the perceptions of mobile learning in medical education. A single case cannot be extrapolated to generalise across other settings; the limit of external validity is well known in case studies. Therefore, the key point is not whether a single case can be generalised but the extent to which the researcher generates conclusions from the data (Yin, 2009). In that regard, there is an inductive process to interpreting a case study with the opportunity to both generate and test theories (Bryman, 2012).

Setting

This study was conducted at the Medical School of the University of Nottingham, a Russell Group member since 1994. As of August 2018, the Medical School is ranked 23rd out of 33 in the Complete Universities Guide ranking of UK Medical Schools (Bhardwa, 2017). At the time of the study, the main undergraduate course lasts 5 years with 2 years of pre-clinical study before undertaking a bachelor’s dissertation. Following this undergraduate students start Clinical Phase 1 (CP1) in the latter half of their third year. They are joined by Graduate Entry Medicine (GEM) students whose course consists of one and a half years of PBL pre-clinical study before they enter CP1 and continue the clinical stage with the undergraduate students. CP1 consists of 14 weeks with 7 spent in Medicine and 7 in General Surgery. Students are sited in hospitals across the East Midlands Deanery for CP1. This study was sited at one of these hospitals, the Queens Medical Centre (QMC) in Nottingham.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were purposively sampled for relevance to the research question. There were three participant groups.

Medical students placed at the QMC were approached at the beginning of their CP1 attachment with a verbal presentation by the author during their induction sessions. An invitation was sent via email to students after the halfway point of the CP1 attachment including a description of the study. Students who replied were placed into focus groups with a suitable date and time for the interview to take place. It was felt their perspectives at that stage of the course would offer relevant insight as to the most junior group on a clinical attachment with recent experience of the pre-clinical years.

All medical educators employed by the University of Nottingham as Clinical Teaching Fellows at the QMC were sent an invitation via email along with a description of the study. Those who replied were offered a suitable date and time for the interview to take place. It was felt they would offer an experience of day to day teaching and the related practicalities and methods.

Senior medical educators were purposively sampled due to their experience in assessment, e-Learning, curriculum design and the regulatory requirements of the GMC. A senior medical educator was defined as anyone employed by the University of Nottingham Medical School in a director or lead capacity. Those purposively sampled were sent an invitation via email along with a description of the study. Those who replied were offered a suitable date and time for the interview to take place. Engagement with the project was voluntary for all and participants had the option to withdraw at any time.

As medical educator recruitment became an issue for this study it was felt prudent to keep to the individual interview model for these subjects. Literature detailing medical educator perceptions of mobile learning is particularly sparse as discussed earlier and it was felt an individual interview model would allow more exploration of each subject’s lived experience. There was also a concern to avoid any professional friction or seniority hierarchy which may have resulted from a focus group of educators. Finally, it was also felt that the teaching ethos of an individual educator is a personal matter. Peer discussion in a focus group may coerce members to offer views they feel cultural appropriate (Bryman, 2012) and not their actual views. An individual educator’s perception of teaching was therefore felt to be better explored in an anonymous interview.

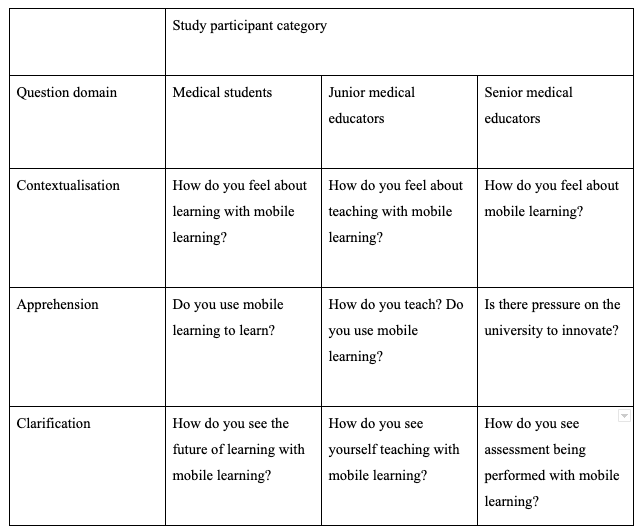

Data collection

Data collection was through focus groups of students and interviews with educators. During the initial stages of this project, it was intended to perform interviews with both groups of participants. However, following the recommendations in the literature of student bodies becoming involved in the formation of mobile resources it was felt to be sensible to seek the perceptions of focus groups of students. Focus groups allow researchers to study the ways a particular group makes sense of a phenomenon especially if members of the group probe and challenge each other’s opinions (Bryman, 2012). Focus groups also relinquish a degree of control from the interviewer to the group, allowing them to set the agenda to some extent with regard to priorities. This was also felt to give a realistic representation of the recommended medical student groups.

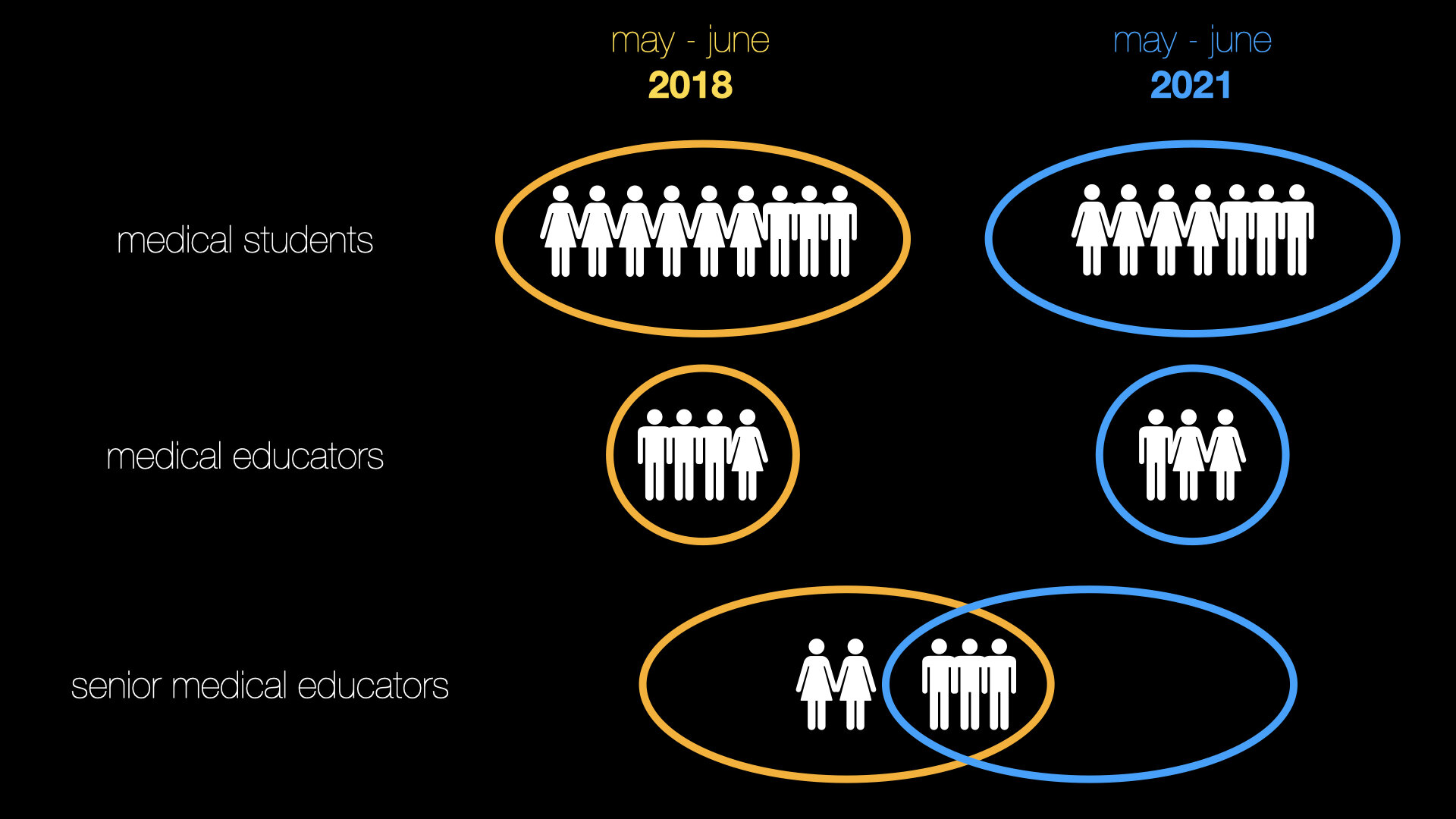

Interviews were conducted in various sites at the Queens Medical Centre between May and June 2018 in the first round and between May and June 2021 in the second. In the first round, the following interviews were held:

Two student focus groups comprising of 9 third-year medical students in total. 4 medical educators and 5 senior medical educators were interviewed individually.

In the second round, the following interviews were held:

Two student focus groups comprising of 7 third-year medical students in total. 3 medical educators and 3 senior medical educators were interviewed individually. The three senior educators had been interviewed in the first round as well.

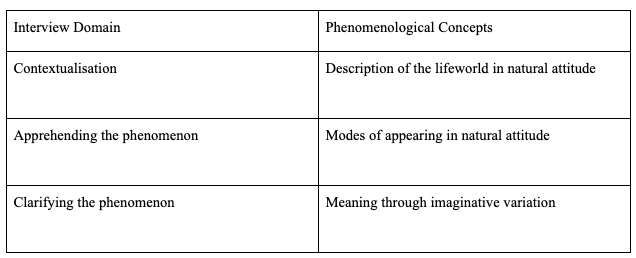

Although the interviews were anonymous participants' basic demographics were recorded (gender, age and whether they had received education outside of the UK). Both focus groups lasted 60-70 minutes with each educator interview lasting up to 40 minutes and were conducted by the author using Bevan’s format. Interviews were semi-structured using a question guide based on contextualising, apprehending and clarifying the phenomenon of mobile learning.

Interviews were digitally recorded, anonymised and transcribed verbatim. Audio recordings of interviews and transcripts, once produced, were securely stored on an encrypted USB drive. No interview was rejected.

It’s been argued that any form of interviewing develops a structure regardless of intent and to allege otherwise is not accurate (Mason, 2002). Therefore a semi-structured questioning style was decided upon ensuring that key themes were explored with the opportunity for elaboration and deviation as necessary. The right questioning format had to be defined early on.

Any interview format in phenomenological research must be kept practical (Bevan, 2014). A suggested format for semi-structured interviewing is based on key concepts within phenomenology: the participant’s description of the phenomenon, their natural attitude and their lifeworld view, the modes of the phenomenon appearing in day to day life, reduction and imaginative variance (Bevan, 2014). These key concepts are divided into three domains of questioning, contextualisation, apprehending the phenomenon and clarifying the phenomenon (Bevan, 2014).

Question selection

Through contextualisation the participant reconstructs and describes their experience in a form of narrative. It is possible to ask for descriptions of places or events, actions and activities (Spradley, 1979). This method fits with previously established processes such as Giorgi’s description and interview (Giorgi, 1989) and Seidman’s focused life history (Seidman, 2006).

Apprehending the phenomenon focuses attention on the experience in question. As Bevan argues, different people will experience the same phenomenon in different ways and the interviewer cannot predict how they will choose to express themselves. Therefore descriptive questions should be supplemented with more structured questions to add depth and quality to the information gathered (Spradley, 1979).

Clarification of the phenomenon is through imaginative variation. Usually, imaginative variation is a core part of phenomenological analysis as described by Husserl (Husserl, 1970) and Heidegger (Heidegger, 1962) to imaginatively vary the elements of an experience to clarify it (Husserl, 1960) rather than the interview process. Bevan argues that by including it during the interview process we can add clarity by explicating experiences. The format of three domains of questioning allows the interviewer to choose a structure of core questions. This appears a very practical approach that lends itself easily to this project.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed by hand as described by Moustakas (1994). First, all the transcripts were read as part of the initial exploration. They were then annotated as themes and relevant statements were found. These themes and statements were lifted for each participant to form the clustering and horizontalisation for that individual. This was then used to form a textual description for the individual participant in question. These were then compiled to form a composite description for each group of participants: medical students, medical educators and senior medical educators. Reflexivity was performed before each stage.

These composite textual descriptions formed the basis of analysis of the participants’ perspectives of mobile learning. Further analysis was performed on the thematic grouping of invariant constituents across all the participant groups. This analysis primarily focused on the invariant constituents as they related to the emergent themes discovered in the literature review regarding mobile learning in medical education as described earlier as well as the specific research voids:

Factors influencing students’ use and perception of mobile learning

Factors influencing educators’ use and perception of mobile learning

Participants’ perceptions of social media in medical education

Digital literacy and experience with mobile learning in clinical practice

Experience with collaborative mobile learning

Potential of student engagement with mobile resource design

Impact of COVID-19 on the above (for second round only)

Any other emergent themes during the study were also to be analysed. As per the rationale of hermeneutic phenomenology the author’s own reflections were included as part of the analysis.

Results

Selection Criteria

First round:

Two focus groups and nine interviews were conducted between May and June 2018 and all were identified as suitable for the study. 16 third-year medical students arranged to attend one of the focus groups, ultimately 9 attended. 6 medical educators arranged interviews but 2 pulled out due to work commitments and an alternative time could not be found. All 5 of the senior educators purposely sampled agreed to interview.

Second round:

Two focus groups and nine interviews were conducted between May and June 2021 and all were identified as suitable for the study. 21 third-year medical students arranged to attend one of the focus groups, ultimately 7 attended. 3 medical educators arranged interviews and attended. All 3 of the senior educators purposely sampled agreed to interview.

Descriptive Data

First round:

In total 18 participants were included in this study. For the purposes of anonymous analysis in the transcriptions medical students were labelled Medical Student A-I, medical educators were labelled Medical Educator A-D and Senior Educators were labelled A-E.

In total 13 participants were included in this study. For the purposes of anonymous analysis in the transcriptions medical students were labelled Medical Student J-P, medical educators were labelled Medical Educator E-G and Senior Educators were labelled A-C; being the same labelling as for the first round.

Clustering and Horizontalisation

Clustering was performed based on themes in the literature and which may have emerged during the course of the interviews. Based on this horizontalisation was performed extracting the invariant constituents for each participant. All invariant constituents were then used to form the textual description for each participant. The textual descriptions for each participant were used to form the composite description for each participant group; medical student, medical educator and senior educator.

There were six key themes explored amongst the participants’ invariant constituents based on themes in the literature review as well as voids in the research being examined by this study. These were:

Factors influencing students’ use and perception of mobile learning

Factors influencing educators’ use and perception of mobile learning

Participants’ perceptions of social media in medical education

Digital literacy and experience with mobile learning in clinical practice

Experience with collaborative mobile learning

Potential of student engagement with mobile resource design

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of mobile learning (for second round only)

Early on in the analysis process it became apparent that there were a number of emergent themes across the transcriptions. These were:

Mobile learning as perceived as a field of pedagogy

The future of medical education

Assessment with mobile resources

During horizontalisation the key invariant constituents which were felt by the author to capture the essence of the phenomenon being studied (Moustakas, 1994) were included in the composite descriptions so to allow greater reflection of the life experience of participants. The composite descriptions are presented with headings for these emergent themes and their key invariant constituents.

Composite Descriptions: First Round

Medical Students

Perception of mobile learning

All of the students considered themselves positive toward mobile learning to varying degrees. Students felt mobile learning served as a supplement to more traditional teaching.

Medical Student C

“I think it's something that you'd use to supplement your learning, not something that you'd use independently to sort of teach yourself from scratch”

There was agreement amongst the students that they would not engage as well with mobile learning as with more traditional learning and anticipated issues with discipline and motivation.

Medical Student F

“Personally I could do with like a teacher stood behind me like whipping me to get me to work.”

Factors influencing use of mobile resources and experience of collaboration

Recommendation either from a medical educator or a peer was needed before the students would use mobile learning resources.

Medical Student B

“ it's pretty much recommendation for me it's like what I've heard from others are good I just used those ones I don't particularly sort of go around looking for new information I just use what's told”

Only one student mentioned themselves recommending a resource to other students. No student had used mobile learning for collaboration with other students, however, they did see the potential to use mobile learning for collaboration. There was a preference for face-to-face contact with educators and other students.

Medical Student C

“I don't think the platforms I've seen truly compare with just like being sat around a table with someone”

Digital literacy

Students agreed that digital literacy was an important skill for doctors. Students had seen mobile resources and devices being used clinically by doctors of different grades. This helped their confidence when it came to using the same resources and devices. There had previously been an assumption that using a smartphone in a clinical environment would be unprofessional. Two of the students mentioned smartphones being banned at their school.

Mobile resources and stage of medical school

It was felt that the clinical phase of the course provided motivation to use mobile resources due to an urge to seek out extra information to avoid negative consequences such as falling behind in knowledge. As a result it was felt that mobile resources are best used in the clinical phase and would be too advanced for the pre-clinical years. Students were also concerned about more junior learners being anxious without more traditional learning.

Medical Student I

“I think the one difficulty with online resources is that they are sometimes designed for people at a much higher level than we are. So I think even now sometimes using them I can feel a bit overwhelmed”

They voiced concern regarding objectives and other expected standards which contact time seemed to assuage. It was felt that mobile learning in comparison might increase anxiety unless standards were explicit or even demonstrated, such as with a video.

Medical Student I

“I think a really helpful thing would be some kind of consensus on clinical skills”

Current use of mobile learning

There was a difference in the students between those who felt they had used more mobile resources since starting CP1 and those who were using fewer. Those who were using more pointed to the opportunistic and practical nature of mobile resources.

Medical Student G

“it's really easy to find things using your phone basically and it everything has to be accurate so you can just take out your phone and like search up NICE guidelines”

Those who were using fewer did so because there were recommended textbooks for the course they were using instead. However, it was noticed that some students described using their smartphone in a clinical environment but did not consider this as mobile learning as they were in the environment at the time.

Medical Student D

“it's been a lot more focused on being on the wards and just trying to respond to what you find there and that necessarily is something that has to be done in person. Not at a distance.”

Some students did search for mobile resources such as smartphone applications for revision. However, use was short lived due to a variety of reasons such as being from the USA or poor usability. Consistent use of resources was linked to recommendations from educators and repeated use during teaching sessions. The BNF application being used during Therapeutics sessions was mentioned by several students as an example of this.

Perceptions of social media in medical education

Discipline was also considered to be an issue in using social media for education. Students were generally against using social media in education. It was felt that any mobile resources would require oversight and facilitation from medical educators.

Medical Student G

“I can't really imagine using social media for educational purposes”

University mobile resources and access to technology

Students felt competent in their skills using mobile resources and accepted that there was an assumption from the university that they would be able to use mobile technology adequately. All agreed that digital literacy was an important skill for doctors but it was also felt skills didn’t need to be too advanced and one student had observed a ward round being held up due to technical issues. One student with prior experience with mobile resources was disappointed in the quality of resources he’d seen in the clinical setting.

Medical Student D

“coming into this world I was absolutely amazed by how primitive a lot of it is”

Another student said her non-medical friends had been surprised at the degree to which she could progress on her course via online learning rather than through direct contact.

Medical Student A

“friends and family they were a little pretty shocked that...could've actually just do University from a bedroom just listening for them online if you wanted to. “

They were negative regarding university mobile technology in particular about correct information and reliability. Students felt any future resources would have the same technical issues.

Medical Student G

“I’d just be genuinely surprised if the university managed to put out an app that actually worked”

However, it was felt that the university and educators should be creating resources. Standardised clinical examination examples were seen as one area where resources would be very useful.

Medical Student B

“the university should definitely be doing more apps and so guides and things I think are clinical skills teaching in first and second year was a bit hit and miss so that other universities have for YouTube videos with exactly what they want online. So you could watch them and know exactly what you need to do but here it's sort of like here's a checklist.”

It was felt that mobile learning and e-Learning both aided uniform learning across different sites and helped create a universal experience. It was felt that in order for students to fully utilise any mobile resources the university would have to consider equipment and previous experience of a lack of support in this area was reported. No student suggested or mentioned being consulted by the university prior to any new resources being released.

None of the students valued university innovation as a consideration during applying and instead looked at reputation, course design and the pass rate. One student felt that there needed to be a session on available mobile learning resources at the start of CP1 induction. It was felt that the university needed to be better at signposting resources.

Reliance on mobile devices

There was agreement that basic knowledge is needed as a doctor but beyond that further information could be accessed as needed and this was a skill that needs to be taught. However, there was concern about becoming too reliant on technology.

Medical Student A

“if you can't function without having something in your hand like a phone then that's not really going to be sustainable long term”

Medical Student G

“ why do I need to remember the order of drugs to give for like hypertension when I can just search it up?”

Design of learning session based on mobile learning

It was argued that any course based on mobile learning would not be radically different from other teachings that the students had experienced in particular Anatomy in the pre-clinical years and Pathology and Therapeutics in CP1. In Anatomy and Pathology, there is central teaching with extra resources for self-directed learning. Some students felt this model encouraged them to learn whilst others felt they did not have the motivation to make the most of opportunities in this way but still saw the value in it. In Therapeutics, the sessions are based on problem-solving and using the British National Formulary (BNF) application to access information relevant to the case being discussed. These sessions were mentioned in particular as a reason why students had accessed mobile resources.

One student had experienced the flipped classroom at school and felt there was a similarity. Students were mixed in their support for the flipped classroom. This was linked with trepidation regarding discipline and motivation of self-directed use of mobile resources in general. However, it was felt that mobile resources might allow closer oversight of progress.

Medical Student A

“it's just a risk of it all becoming too much online and just, yeah need some kind of interaction at the end of the day like you need to be able to talk to a patient”

Medical Student D

“I certainly don't trust myself... going more mobile doesn’t necessarily less oversight and potentially, possibly an earlier lighting up issues.”

Medical Student F

“the sessions that I take most away from are the ones that I've...I've done all the further reading before.“

Students felt adopting mobile learning was an acceptance of social trends regarding smartphones and other mobile technology. Students saw it being used in simulation and clinical decision making or to look at cases before then discussing findings in a traditional classroom setting. Formative assessment was also suggested. It was felt it would be too overwhelming in the pre-clinical course and would work best in small groups.

In appraising online resources some students did use skills taught to them as part of their course. Others used common sense and chose resources by reputation. Students did use resources not approved by the university such as Wikipedia but as a starting point and not as their only resource.

Medical Educators

Mobile resources in clinical practice and in teaching

All of the medical educators used either online or mobile resources as part of their clinical practice for quick reference. The majority (three) of the medical educators used mobile resources as part of their teaching either in a classroom or ward based environment. They mentioned that this reflects real life practice and prepares students for working as a doctor. Their attitude towards mobile learning was predicated on their own use.

Medical Educator A

“anything I’ve used or had experience of I would recommend and I found easy to use, yeah I’ll just recommend to people”

One educator discourages the use of mobile devices in her sessions.

Medical Educator D

“in the classroom, I have to say I'm not a massive fan of mobile phones because I see students on Facebook, Instagram and texting...I do think that it ultimately does distract you from what is going on in front of you”

Educators who didn’t regularly teach using mobile learning described themselves as “old fashioned” in their outlook.

Medical Educator C

“So I would probably say I'm a bit more old-fashioned...I'm still probably more a textbook kind of person”

Medical Educator D

“So, I think I'm probably bit old-fashioned in that no not really I know that some of my other colleagues at induction will recommend certain apps and things and I have to say that I don't. And that's because I don't use them myself”

Practicality, the amount of knowledge available and the rate of change were also factors in choosing to use these resources in both teaching and clinical work.

Medical Educator B

“I think the best way to learn to use technology is often by necessity”

Factors influencing the use of mobile resources in teaching

Mobile resources were recommended if they had been used in the educator’s own clinical work and so were trusted and from a validated source. The mobile resources mentioned were published from renowned books or websites that predated them.

Medical Educator B

“I tell them to download the BNF on the first day of placement...the reason I recommend those apps is because I use them as a junior doctor and they need to get comfortable using those different modalities of accessing information”

The medical educator who didn’t recommend mobile resources did so because she didn’t use them in her own practice rather than for an educational reason. One medical educator believes that without technology doctors will struggle to stay relevant.

Medical Educator C

“I've seen the most senior consultants pull out their smartphones and use it for very specific things. Research changes so quickly...the ones that are slow to change others ones that are slow to stay relevant”

There was a discussion about how mobile learning was impacting students’ relationships with knowledge.

Medical Educator B

“I think a lot of the students take a lot of knowledge for granted and knowledge is a bit more

disposable...how you get the information becomes the key cornerstone of it rather than the actual information itself.”

Medical Educator C

“think there are some limitations in it that some students would be reluctant to get too deep into the actual knowledge...”

Digital literacy and designing teaching based on mobile learning

All of the medical educators agreed that digital literacy is a key skill for doctors and that access to and proficiency with mobile technology were expected in medical students.

Medical Educator B

“we’d be doing our students a disservice if we didn’t improve their computer literacy as well”

It was mentioned that support is needed for medical educators to produce their own resources. Three of the medical educators had experienced issues with using mobile technology in their teaching, mentioning Wifi failure and difficulties with information governance as reasons sessions hadn’t gone as planned.

One medical educator felt unsupported by the university when trying to set up a new teaching programme based on mobile learning as they wanted something more tangible and traditional. One of the medical educators always has a backup plan when a session using technology is planned due to a fear of issues arising.

Social media in medical education

One of the medical educators was enthusiastic about using social media in education as the best way to keep up with developments in Medicine.

Medical Educator A

“Yeah I think it’s a good thing…because advances in medicine and things are changing sorted so rapidly, it seems to be really the best way to sort of keep up with those advancements”

Other medical educators were hesitant. It was believed that social media posed the challenge of students being able to vet the information they find. It was felt that this is not a skill taught well to students. There was agreement in doctors having some form of social media presence and using it to share information. The risks of professional behaviour and public image were mentioned, with social media activity as a student having potential repercussions even when graduated. However, the use of social media as a community was mentioned as a benefit.

Medical Educator D

“I have very mixed feelings about social media in general, in terms of our lives as doctors. Because I think we are, whatever you put out is exposing you to a certain amount of risk..I do think it's a valuable resource and the other thing that I suppose that Twitter specifically gives you is a sort of a sense of community as well. And medical school can be incredibly isolating, it can be very lonely sometimes.”

One medical educator surmised that that educational and research in the future might change as a result of students now being so accustomed to and experienced with social media.

Medical Educator C

“the question will come in about five or ten or fifteen years’ time when the people of this current age other people that are making their decisions. When they're consultants and they're the ones that's putting out information are they then going to be susceptible to was kind of sensationalism to get the message out and cut corners on research or discussion or context”

Collaboration using mobile learning

One medical educator was concerned about him and his colleagues working in silos and needing to collaborate further. Although there was agreement about using mobile learning to access up to date information there were no further comments about sharing information across mobile resources.

Medical Educator B

“I think if we are to innovate, we need to have a more networked approach between the different educational providers...we’re replicating the same work that’s being done in multiple different hospitals open around the world”

Role of the educator and mobile learning

All of the medical educators saw themselves in some kind of guide or signposting role when they teach.

Medical Educator D

“I'm very much there to kind of guide”

All emphasised that they are not the source of all information. They all bring their own clinical experience to teaching emphasising the nuances and differences from a theory that can happen in real life. This came out as one of their perceived strengths of the teaching fellow role. These nuances were felt to be important to clinical medical education. One medical educator felt that the traditional teacher role didn’t suit modern Medicine.

Medical Educator C

“I think because actually the unique role that our current role as clinical educators is that we are more, we are closer to them from a teacher learner role than a traditional classroom environment teacher learner role. Whereby they would always look up to the teacher and expect them to know everything , that’s not what Medicine is and again that rose back to what we how we practice clinically”

Perceptions of mobile learning

Reaction to educators focusing on mobile technology was mixed. One medical educator felt teaching through mobile learning wasn’t vastly different from situated learning or social learning theory whilst another felt it sounded like PBL.

Medical Educator B

“situated learning and potentially social learning theory, because we’re using technology to

communicate between people. It's just changing the format of the communication. And then

situational learning we’re just placing the learning activity in a different situation with different technology. But it’s still an information exchange, it just happens since before educational theory were invented”

Medical Educator D

“certainly my understanding of PBL is that you're given a problem and you're asked to solve it and you're shown potentially where you might look for that information. So on the face of it sounds very similar”

There was general agreement that using mobile learning is well established as an educational tool and that it would work best for the more experienced undergraduate students or in the postgraduate sphere.

Medical Educator B

“For junior undergraduate medical students, they’ve not learnt that level of critical appraisal yet. So, getting them to use resources where it’s not all valid and it’s not over liable information becomes a bit of a dodgy situation in my opinion… It’s not something that we explicitly teach very well in undergraduate medicine for, perhaps using technology is a good way to do it.”

The medical educator who doesn’t use mobile resources felt that her normal approach using real life props such as clerking sheets was similar in principle to using mobile learning just without the technology as it focuses on realism.

There were concerns that weaker students might not engage with mobile learning and that it would be harder to keep an eye on student progress. It was felt that mobile learning would require an element of contact time with more traditional teaching to ensure there is a grounding of theoretical knowledge. One medical educator mentioned her own opinions regarding the cost to students of medical education and the expectation of contact time that comes with this.

Medical Educator D

“If I’m paying for something I’d quite like that to be delivered to me.”

Designing teaching sessions based on mobile learning

It was felt that mobile learning would work better in smaller groups of students. Proposed sessions involved simulation to replicate real world practice or in case based discussions looking up guidelines and treatment algorithms. One medical educator suggested running the session similar to PBL.

Medical Educator B

“I think like using a PBL type session, would make a lot of sense”

Another proposed session was similar to the flipped classroom which two of the medical educators had used with good results. One had encountered as a student himself.

Medical Educator A

“I’ve had experience of it as a learner, quite a long time ago and it was very different then...whereas, now because everything sort of is more to hand, I think you’ve got more ability to make it more interesting and more interactive...some sort of interactive learning, after the teaching and then come back and stop discuss that...then feedback on what they’ve found or they could do it through case based discussions or something”

It was agreed that students usually brought correct information to flipped classroom sessions without much direction needed. It was also felt that mobile learning activities would follow a more traditional didactic session and would need to be explained to students as a concept.

Medical Educator C

”would not be the first thing you do, but it may be the third or fourth type of thing you would do. So you would use it to build on top of previous knowledge that you gained from a different aspect or something”

Concerns were voiced about how information could actually be covered in this session with one medical educator feeling it would cover more behavioural activities than knowledge.

Medical Educator C

“I guess you just have to be careful of how much information from a knowledge one of you are going to try and give in this sort of setting….but I guess it would be more from work from a behavioral point of view that I would try and plan a session. And less on hard cold facts trying to get people thinking in a particular way as opposed to these are the set numbers I was you’re able to learn”

No medical educator saw mobile learning as completely or mostly replacing traditional learning exercises. No medical educator suggested involving medical students in the creation of resources.

Senior Educators

Student engagement in designing mobile resources

One senior educator had noticed a push for resources from students and suggested forming a focus group with them.

Senior Educator E