Earlier this year I submitted an abstract to the Association for Simulated Practice in Healthcare (ASPiH) conference about my work on the application for medical students in the Emergency Department.

On 3rd August I received an email back informing me I’d been accepted for a poster presentation. Joy was then met with not a small amount of trepidation as I read further “You should plan to speak for 3 minutes with an additional 2 minutes for questions.”

3 minutes?

180 tiny seconds of time to talk about my project, my baby?

I’d presented for 10 minutes before but this was something else in terms of brevity. So I tried to have a process. This is my process, I’m not saying it’s perfect and there’s still things I’d want to change but it’s an example of how to approach the problem of getting your message across in a short period of time.

The idea of any talk is to engage, inspire and inform, That ratio can be changed around; the longer your talk you more you can inform about at the risk of losing engagement and inspiration. Obviously with only 3 minutes I was going to have to cut on the informing and focus on engagement and inspiring. I needed another way of informing the audience.

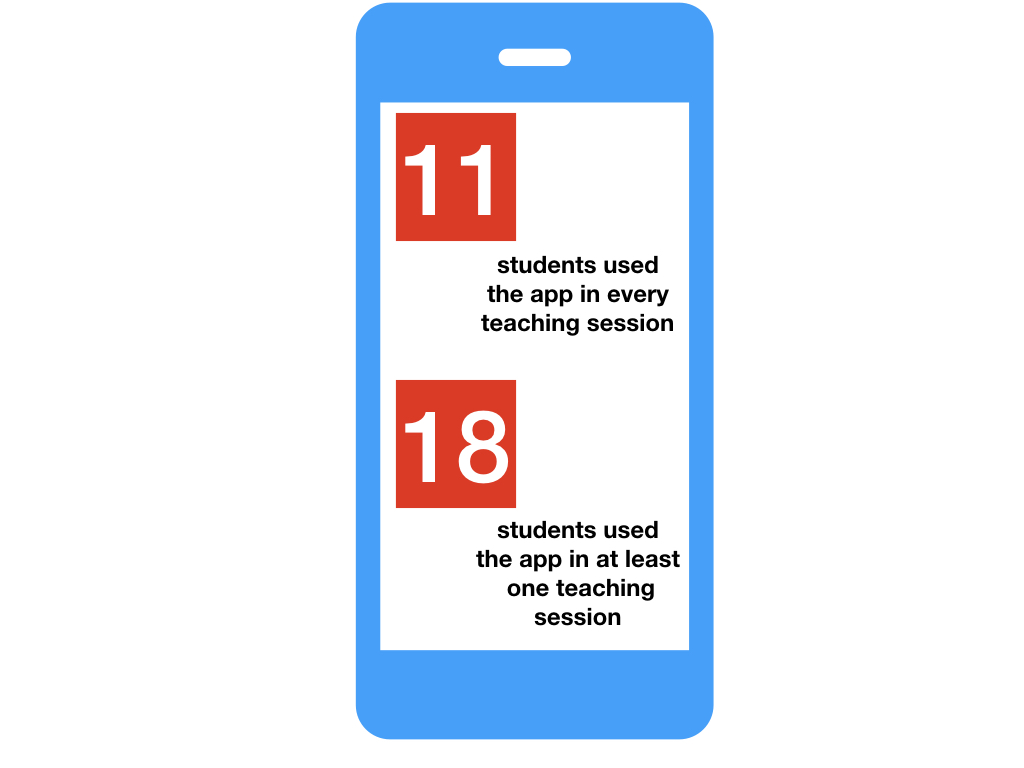

So, I wrote a blog. This step helped me know the subject and clarify the key points along the way. What’s the killer and what’s filler? What is nice to know but what is absolutely essential about your message? By doing this I realised I had three (always a good number) key points I wanted to highlight: the app was easy to make, it flipped the classroom and blended learning and that students value opportunities to practice digital literacy in simulation.

My talk would therefore be used to get those three points across and hopefully inspire my audience to look for the blog to read more.

Once the blog was written (and that took a long time) and I’d realised what the purpose of my talk would be I decided to see this as an ‘elevator pitch’ similar to those used in business as a format of engaging potential employers/investors in your project. Essentially you imagine you’re in the lift with the person you want to impress and you’ve got the time it takes to go from the ground floor to the top to sell yourself or your product.

With that in my mind I did a few Google searches to find what advice is our there to create an elevator pitch. Unsurprisingly, they’ve made an industry out of this so there’s a lot of information but very little I found useful without needing to pay money. However, I found this blog very useful by Alyssa Gregory. She breaks the process down into stages:

Define who you are are

Describe what you do

Identify ideal audience

Explain what’s unique and different about you

State what you want to happen next

Create an attention-grabbing hook

Put it all together (start with 6)

So I did this. I wrote it out.

And I read it out loud. Slowly and clearly. It came in at 2 minutes 45 seconds. Great! But on reading it out loud it felt flat. And weird. I realised while it was a useful tactic to plan a bit like an elevator pitch the key difference was I wasn’t selling anything. So I did the next step. I practised. With an audience.

This seems perfunctory but it’s key. Only on performing in front of colleagues who I knew would be productive in their criticism did I start to get a sense of what it was like to hear about the application. They could tell me about the ebb and flow and how easy it was to follow my three key messages. There was a rewrite. And another.

Finally, I was lucky in that my poster was on the third day of ASPiH so on the second I was able to watch a poster session and get a feel for the room and see what works and what doesn’t. Clear, slow speech was vital. A bit of humour if possible. Don’t distract with your body language. Look at the audience and not your poster.

There was another slight rewrite and then a lot more practising.

This is what I came up with.

As I said before it’s not perfect but I was happy with it and it seemed to be well received.

I hope this is useful to you and helps if you’ve got a very short presentation to make. Any of your own tips? Anything you don’t agree with? Let me know!