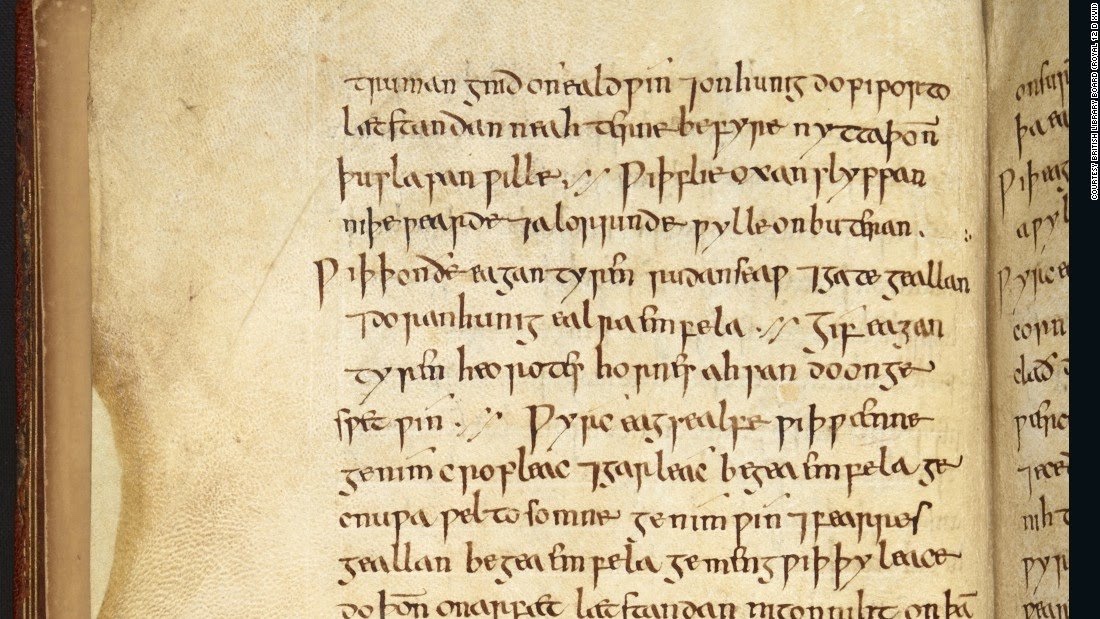

Bald’s eyesalve. A facsimile of the recipe, taken from the manuscript known as Bald’s Leechbook (London, British Library, Royal 12, D xvii).

In a previous musing I looked at medieval Medicine and common theories of illness and cure at the time. Medieval Medicine has a reputation for being backward in contrast to the enlightened Renaissance. This is the story of a pre-medieval medicine and a modern day ‘superbug’.

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was first identified in Britain in 1961. Staphylococcus aureus is a very common species of bacteria often found on the human body which, given the opportunity, can cause infections especially in soft tissues like the skin. Staph aureus bacteria have a cell wall which protects them from their environment. They use a number of proteins to build this wall. It’s these proteins to which penicillin antibiotics bind and stop bacteria from making their protective cell wall (hence them being called penicillin binding proteins or PBPs). Without their wall the bacterial cells die. MRSA gets around this because it has evolved to produced a protein called PBP2a which is much harder for penicillins to bind to and so their activity is greatly impeded.

Like a lot of bacteria MRSA is able to stick together and secrete proteins to form a slimy, protective layer. This is called a biofilm. This means it is able to colonise various surfaces in the community and hospital environment. As a result MRSA is a leading cause of infections acquired in both the community and in hospitals. In fact, there are ten times the number of infections due to MRSA than all other multiple drug resistant bacteria combined. Science has looked at unusual places to find an answer. Enter Bald’s Leechbook.

Bald’s Leechbook was written in England in the 10th century and offers cures for a number of conditions, including infections. In 2015 a study decided to look at one such cure for eye ‘wen’ - a lump in the eye (probably a sty). This was the passage in question:

“Ƿyrc eaȝsealf ƿiþ ƿænne: ȝenim cropleac ⁊ ȝarleac beȝea emfela, ȝecnuƿe ƿel tosomne, ȝenim ƿin ⁊ fearres ȝeallen beȝean emfela ȝemenȝ ƿiþ þy leaces, do þonne on arfæt læt standan niȝon niht on þæm arfæt aƿrinȝ þurh claþ ⁊ hlyttre ƿel, do on horn ⁊ ymb niht do mid feþre on eaȝe; se betsta læcedom.”

This is translated into modern English as follows.

“Make an eyesalve against a wen: take equal amounts of cropleac [an Allium species] and garlic, pound well together, take equal amounts of wine and oxgall, mix with the alliums, put this in a brass vessel, let [the mixture] stand for nine nights in the brass vessel, wring through a cloth and clarify well, put in a horn and at night apply to the eye with a feather; the best medicine.”

Incredibly, Bald’s salve was found to kill MRSA as well as break up the biofilms it forms. This was shocking enough but the researchers found that the salve seemed to work best when the recipe was followed exactly. If steps or ingredients were skipped then the resulting treatment did not work as well. Previous research had shown that individual ingredients such as allium species did have antibacterial effects but these were intensified when used in combination with the other ingredients.

This suggests one of two possibilities. Either Bald randomly threw together these recipes and got lucky. Or there was something of a scholarly approach going on, using ingredients known to work and mixing them together to create something greater than the sum of its parts. I’m not suggesting that all Medicine at the time was correct but as I said in a previous blog, perhaps the medieval period wasn’t such a dark age after all.

This suggests a redrawing of medical and scientific history; previously the scientific method was believed to have been invented by the Royal Society in the 17th century and the first antimicrobial medicine was Lister’s carbolic acid in their 19th century. I’m not advocating a return of 10th century Medicine but instead an appreciate of our forebears who probably knew a lot more than we give them credit.

Thanks for reading

- Jamie