Convergent evolution is a key principle in Biology. Basically, it means that nature will find the same ‘solutions’ for organisms filling similar environmental niches. So in different species with no close relation but who encounter similar environments (say sharks and dolphins) you’ll see similar features (both have fins). The same is true in the history of science. Very few discoveries are actually made in solitude; more often there were several people working on the same problem but often only one gets the fame. For Charles Darwin see Alfred Russel Wallace. For Sir Isaac Newton see Robert Hooke.

We discuss the unsung heroes in the fight against smallpox and variolation (and review wine) in the third episode of the Quacks Who Quaff podcast.

When it comes to vaccination and the conquest of smallpox, one of the most deadly diseases to ever afflict mankind, one name always comes to mind: Edward Jenner. We all know the story: an English country doctor in the 18th century observed how milkmaids who contracted cowpox from their cattle were immune to the far more serious smallpox. On 14th May 1796 he deliberately infected the eight-year-old boy James Phipps with cowpox. The boy develops a mild fever. Later Jenner exposes Phipps to pus from a smallpox blister. The boy is unaffected by smallpox. A legend is born. Vaccination becomes the mainstay of the fight against smallpox. In the 20th century a worldwide campaign results in smallpox being the first disease to be eradicated.

Of course, as we all know, things are rarely this straightforward and there are many less famous individuals who all contributed to the successful fight against smallpox.

Dr Jenner performing his first vaccination on James Phipps, a boy of age 8. May 14th, 1796. Painting by Ernest Board (early 20th century).

Smallpox, the ‘speckled monster’, has a mortality rate of 30% and is caused by a highly contagious airborne virus. It long affected mankind; smallpox scars have been seen in Egyptian mummiesfrom the 3rd Century BCE. Occurring in outbreaks it is estimated to have killed up to 500 million peoplein the 20th century alone. Throughout history it was no respecter of status or geography, killing monarchs and playing a role in the downfall of indigenous peoples around the world. Superstition followed smallpox with the disease even being worshipped as a god around the world.

Doctors in the West had no answer to it. But in other parts of the world solutions were found. With colonisation and exploration the West started to hear about them. More than seventy years before Jenner’s work two people on either side of the Atlantic were inspired by custom from Africa and Asia.

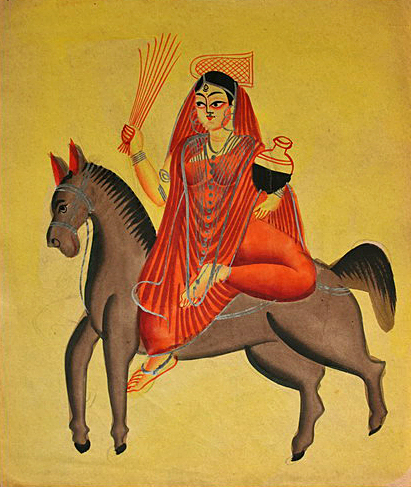

Left: Shitala, the North Indian goddess of pustules and sores

Right: Sopona, the god of smallpox in the Yoruba region of Nigeria

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

In 1721 in London Lady Mary Wortley Montagu the wife of the Ambassador to Turkey who had lost her brother to smallpox having survived the disease herself is keen to protect her daughter. Whilst in Turkey she learned of the local practice of ‘variolation’ or inoculation against smallpox. Pus from the pustules of patients with mild smallpox is collected and scratched into the skin of an uninfected person. This was a version of a process dating back to circa 1000 AD in China where pustule material was blown up the nose of a patient. Mary was impressed and her son was inoculated in Turkey in 1715.

Six years later in London her daughter was similarly inoculated in the presence of doctors of the royal court, the first such procedure in Britain. She campaigns for the practice to be spread.

Cotton Mather

Also in 1721, an outbreak of smallpox is ravaging Boston, Massachusetts. An influential minister Cotton Mather is told by one of his African slaves, Onesimus, about a procedure similar to inoculation. According to Onesimus as a younger man a cut was made into his skin and smallpox pustules were rubbed into the wound. He told Mather that this had made him immune to smallpox. Mather hears of the same practice in China and Turkey and is intrigued. He finds a doctor, Zabdiel Boylston, and the two start performing the first inoculations in America.

Lady Wortley Montagu and Cotton Mather never met, they lived on opposite sides of the Atlantic and yet learnt of the same practice. Convergent medical advances in practice.

Inoculation is not without risk however and Prince Octavius, son of King George III dies in 1783 following inoculation. People inoculated with smallpox are also potentially contagious. An alternative is sought.

In 1768 an English physician John Fewster identified that cowpox offered immunity against smallpox and begins offering the practice of immunisation. In 1774 Benjamin Festy, a dairy farmer in Yetminster, Dorset, also aware of the immunity offered by cowpox,, has his wife and children infected with the disease. He tests the procedure by then exposing his son to smallpox. His son is fine. The process is called vaccination after the Latin word for cow. However, neither men publish their work. In France in 1780 politician Jacques Antoine Rabaut-Pommier opens a hospital and offers vaccination against smallpox. It is said that he told an English doctor called Dr Pugh about the practice. The English physician promised to tell his friend, also a doctor, about vaccination. His friend’s name? Edward Jenner.

It is Jenner who publishes his work and pushes for vaccination as a preventative measure against smallpox. It is his vaccine which is used as the UK Parliament through a succession of Acts starting in 1840 makes variolation illegal and provides free vaccination against smallpox. In a precursor of the ignorance of the ‘anti-vaxxer’ movement there is some public hysteria but vaccination proves safe and effective (as it still is).

Cartoon by British satirist James Gillray from 1802 showing vaccination hysteria

Arguably, without Jenner’s work such an effective campaign would have been held back. As the American financier Bernard Baruch put it, “Millions saw the apple fall, but Newton was the one who asked why.” However, Newton himself felt that “if I have seen further it is because I have stood on the shoulders of giants.” History in the West has a habit of focusing on rich white men at the exclusion of others, especially women and slaves. Any appreciation of Jenner’s work must also include those giants whose shoulders he stood by acknowledging the contribution of people like Lady Wortley Montagu and Onesimus and of Fewster and Festy - the Wallaces to his Darwin.

Thanks for reading

- Jamie